Posthumous Conversations: My Transcendental Experience Taking Ayahuasca with a Shaman

“What is death? What is life? Life without death has no meaning. Life does not exist without death. Wherever there is life, there is death. And we cannot hide from it. Death is a change, a process. It is necessary for life. Western societies have demonized death. But why? Due to fear and ignorance. Because there’s something to be afraid of after death? What is it? What is God? They are truly afraid of God, and He is life itself. So they stay away from death and by doing so they stay away from life as well.”

Resolving that I’d held it down for as long as I could, I broke from my half-arsed half-lotus position, clasped my plastic red bucket like a diminutive inmate would his dinner tray, left the circle of drinkers, and hastily made my way to the toilet. As soon as the bathroom door shut a powerful deluge of brown, fetid sludge forced my mouth agape and, resonating on the plastic like fingers tapping a bongo, splashed into the bottom of the bucket. The receptacle turned warm and emanated a rancid stench that smacked my face like a passing convoy of garbage trucks. I’d just barfed an extremely potent entheogen, infamous for its ability to evoke profoundly spiritual visions, deeply personal psychological insights, and intellectual ideations. I placed my oral potty in the washbasin, and, with arms akimbo, I looked up from the gunk and found myself face to face with an invalid drooling into a large, red spittoon. Staring at my reflection while completely compos mentis I wryly thought, ‘Is this it then?’

In the traditional Amazonian shamanic context, ayahuasca (aka La Purga, Abuela, Grandmother, Spirit Vine, Vine of Death) is a hallucinogenic beverage used for spiritual, religious, and medicinal purposes; it is often described as a window into the sacred cosmology of magic, transcendent experience, and healing. For readers preferring a description sincere to the traditions of enlightenment thought: it is a tea typically obtained from the vine Banisteriopsis caapi and shrub Psychotria viridis, where B. caapi contains beta-carboline alkaloids with MAOI (monoamine oxidase inhibitor) action, while P. viridis contains the hallucinogen N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT). However, DMT is not active orally because it is enzymatically destroyed, but its combination with the MAOIs from B. caapi renders it orally active and is the basis of the psychotropic action of ayahuasca. The plants used are native to opposite ends of the Amazon jungle, an area almost three-quarters the size of Australia. This fact has baffled anthropologists trying to fathom how it came to be that ancient tribes developed the botanical knowledge to locate, identify, and prepare something so medicinally complex and powerful.

Banisteriopsis caapi.

The practice of utilising different plants to heal various illnesses has been widespread among numerous indigenous tribes throughout the Amazon Basin for millennia. Contrary to western medicine’s penchant to dichotomise ailments of the mind and body—a practice producing a glut of separate practitioners dedicated to segregated parts of the whole (e.g., doctors, therapists, psychologists, priests, spiritual advisors, psychotherapists, and counsellors)—shamanic healing treats a person as a single whole, where physical, spiritual, and psychological aspects all interrelate with one another. For instance, psychological torments such as guilt and shame may insidiously plague a person long after the emotional symptoms have subsided, and they can often manifest as a full-blown, chronic physical illness.

Psychotria viridis Chacruna.

The process of healing chronic illnesses with shamanic knowledge has recently been documented in the film The Sacred Science. Released in 2011, the documentary focuses on a sundry group of eight patients who suffer from various chronic psychological and physical illnesses. They travel to the Amazon rainforest to undergo an intensive healing program under the guidance of local shamanic healers (aka Medicine Men, Curandero, Shaman). The participants are given a combination of plant medicines—including ayahuasca—and intense spiritual exercises, in the hope of confronting and mitigating deep spiritual and emotional issues, therefore eliminating any fabricated barriers between their physical and mental states.

The journey I undertook, however, didn’t entail exhausting my local IGA of heavy-duty insect repellent, packing bags and travelling to the Amazon to ingest the sacred tea amongst indigenous Peruvians and pasty, psychotropic-seeking tourists. Nor was I (consciously) attempting to ameliorate any burdensome psychological or physical malady. Ostensibly, I agreed to the ayahuasca ceremony invitation out of sheer curiosity. However, I’ve always felt shrouded by an overwhelming and often debilitating detachment from the values, morals, metaphysical, theological, and existential systems of my milieu, and I have often desired a connection with something deeper that would transcend dialectic consciousness and provide me with a strong philosophical footing. I was after a quasi-religious experience void of theological undertones, void of submissive prostration to a merciless ethereal deity who preys on the absurd human condition and its credulous penchant for blind faith. I’ve been teetering precariously on a metaphorical fence of agnosticism, neither willing to worship nor eulogise God as Zarathustra did. I was reluctant to accept as dogma the disenchanted perspective provided by science, and I was dissatisfied with the dearth of options available in western culture to someone searching for a natural and holistic form of guidance that doesn’t charge by the hour and revert to the prognosis that my anal complex is the fountainhead of all my woes.

So there I was, at home, nursing my third Heineken while waiting for the convoy of cars that was transporting the ceremony invitees toward our ersatz Amazon: Geelong. I’d been looking forward to this day since receiving the following enigmatic text: ‘You have been invited to a ceremony, I will contact you with details soon’. Two days post-text I was sitting with my tattooist at our local speakeasy, eagerly enquiring whether there was any preparatory rigmarole I needed to endure. ‘Just don’t drink alcohol the week prior; fast; and eat only rice and raw vegetables from the antepenultimate day. And try meditating.’ I went home and looked up ‘antepenultimate’. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV listed my self-identified idiosyncrasies under the heading Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, so that ruled out meditation. I forgot about the fasting, although on the penultimate day I’d eaten nothing besides a lotus. As I cracked open my fourth Heineken, the convoy finally arrived.

Geelong: Pulling into the front yard of the house where the ceremony was to take place, images of Peter Fonda’s Paul Groves rapidly came to mind and just as quickly subsided. It was dusk, and I could tell we were a fair distance from the city because the sky’s crepuscular reflections on my windshield were pissing me off. White Jesus was standing on the front porch greeting people with hugs and familiar adorations; it seemed cuddles were status quo and kisses the new hello. The suburban saviour was wearing a brown Alpaca poncho. As I approached the messianic figure, I deduced that he wasn’t white Jesus and the halo emanation was, in fact, a mere temporal porch light. It was clear I had no idea what I was doing nor what to expect. As a neophyte in the art of greeting shamans, I tried to avoid committing any kind of introductory faux pas and advanced with an outstretched arm, as if to say: this is my hand; it wants to be shaken. Instead, the shaman used my hand as a line and reeled me into a warm and surprisingly tolerable embrace. ‘I like this guy,’ thought I.

There were about thirteen of us in total, a motley crew sporting enough skin ink among us to create a graphic novel. A few strangers (I considered those that arrived as part of the convoy to be known to me, regardless of the fact that I had already forgotten their names after the hasty introductions exchanged during a fuel stop) were already patiently seated around the periphery of a large rug, on which was placed an array of indigenous looking instruments, including the didgeridoo, singing bowls, and an acoustic guitar. Exchanging a few perfunctory pleasantries, I sat between a young woman from Melbourne, for whom this ceremony was her third, and an older woman of about sixty—a self-confessed ceremony veteran who chortled treacherously upon learning that I was an ayahuasca virgin. ‘How reassuring,’ I thought with sinking gut.

This brings us—almost, at least—to the invalid drooling over the red bucket. I was feeling slightly vexed, having endured an unpleasant side effect of ayahuasca yet bereft of any cognitive effects. Prior to ingesting the psychotropic, the shaman had advised us against actively seeking out the plant’s wisdom and instead to let ourselves be receptive to it. The most common types of knowledge encountered are factual knowledge, when the drink enables people to obtain specific information about their past, the biography of others, privileged information about the natural world, and even directly observe other places and times. Then there is psychological knowledge, which consists of personal insights, self understanding, and novel psychological comprehension. Knowledge related to nature and life is where drinkers establish a unique, close link to nature, with insights and a profound understanding concerning flora, fauna, and global biology and ecology. Ayahuasca often generates philosophical and metaphysical ideations and reflections, even among philosophical dunces. Drinkers can also feel a sense of wellbeing, overall comportment, and wisdom, enjoying more stamina and greater existential harmony. Most often, however, non-ordinary states of mind are encountered, doors of perception are opened, and the antipodes of the mind are explored. At the time, however, I had no idea what I was supposed to be receptive toward. I felt like a flat-screen television searching for a signal through a shoddy coat-hanger. So I decided it was only fair that I boost my feelers and have another dose …

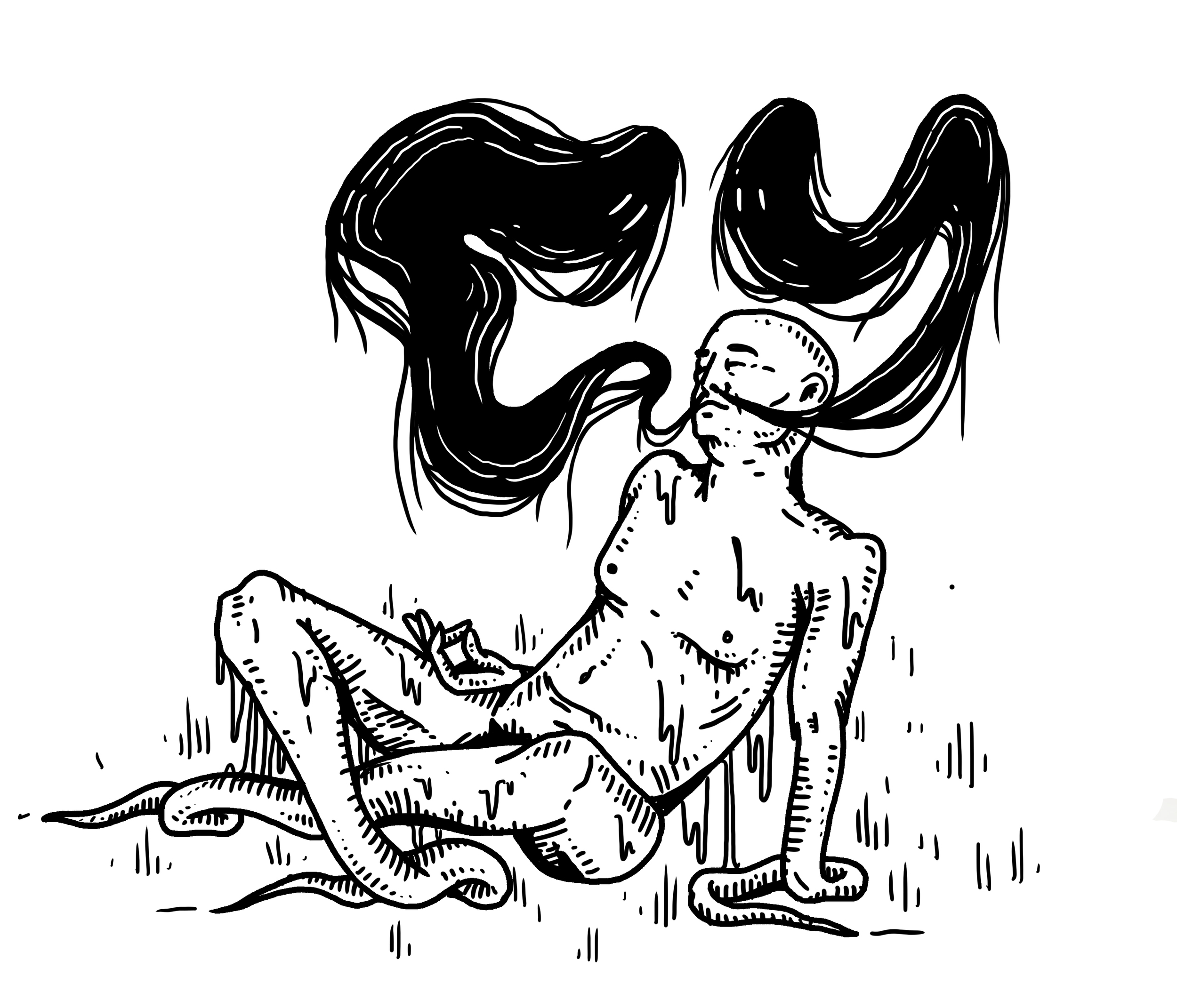

The work of Paulo Jales: http://paulojales.wordpress.com/

Twenty minutes later I found myself whispering in astonishment, ‘Where is this placcsssssssss?’ My immediate surroundings were suffused with a billowing, nebulous glow, not unlike a photo of flowing water for which the shutter was left open, exposing the film for several minutes. The other participants were mere radiating blobs. I had traversed into another reality where visual and audio modalities were redundant: my face had bust asunder into large, hovering fragments; one eye felt as though it were above what I perceived to be my corporeal head, while the other was near my knee. I became synesthetic—inhaling my visions, exhaling what was heard, psychoacoustics gone awry. It was as though I had inhaled the canvas, yet the painting still stood before me—inside my body lay the very foundation of existence, a manifestation of the whole rather than an isolated organism. The shaman’s throat singing tasted like centuries of atavistic dance, movement, and gyration. With eyes shut, iridescent tendrils and tassels with DNA-structured patterns flailed about me, slithering out my mouth with an ambient ebbing and flowing aaaaaaaaaaaaaeeeeeee that morphed into staccato tst tst tst t t t ttttssszzzz ahhhhh. Searching for the right mudra, I rested my hands on my knees, palms exposed. On my left, the young woman sat with her back straight and elegantly gesticulated at a gingerly pace (later I learned she was handing out flowers to rabbits and unicorns). On my right, the older woman was full of astonished love for all things, repeatedly proffering her thanks to what I later learned was mother earth. I was isolated in empty thoughts for some time, the burden of corporeal realities eschewed—like an ascetic meditating in an atemporal monastery. The presence of two distinct spirits converged upon me: as the anonymous apparitions encroached upon my consciousness I sensed that they were my grandfathers, although I could distinguish my mother’s father as having an omnipresence—eventually his benign spirit took up residence within my body and mind (I never met my mother’s father.

Illustrated by Nina Waldron @goatlumps

The Iranian government murdered him several months after I was born because he refused to renounce his faith). He began to bequeath his wisdom, humility, and knowledge; I felt his personality align with mine, and throughout the metamorphosis I observed the similarities I had inherited from him. He had come to remind me that erudition must trump hedonism, that I was on the right path although I may think otherwise, and that I am my ancestor’s descendent, my grandfather’s grandson, my mother’s son. I basked in my grandfather’s presence and esoteric wisdom. It felt as though I had spent an inordinate amount of time smoking Cuban cigars in the drawing room of my family estate, gaining valuable insights into the corporation that was my blood-line and inheritance. This was a benevolent and serious being who wanted to reassure me of the importance and value of the gift of life—one must treat it with respect. He waited for me to speak before leaving, as hitherto I had been silently absorbing everything he imparted. Smiling, I facetiously enquired, ‘But I can still have fun, right?’ And with that he bellowed out in laughter, leaving it to resonate as a vestige of his omnipresence.

Recently, I emailed my mother requesting her to send any information she had surrounding the circumstances of her father’s murder. She sent me an article about my grandfather that my older sister had written in high school. In it, she describes how my grandfather had dedicated his life to the principal teachings of his faith—the unity of humankind and religions, and the establishment of a universal faith. She goes on to say that deep down I know his soul is in the best place now—in the next world. Perhaps, my grandfather received in death what he dedicated himself to in life. And perhaps ayahuasca, as humanity’s magico-spiritual telecommunications network to the next and all other worlds, is here to reassure us that in death there is life.

My Grandfather. (My family still face persecution in Iran, therefore I have refrained from entering my late Grandfather's name as a precautionary measure).

The World Ayahuasca Conference is being held this year in Ibiza: http://www.aya2014.com/en/