Our Bodies, Our Voices, Our Marks thoughtfully captures the endurance of tattoo and tradition

Visitors looking at photographs in Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World. Credit: Ben Healley.

The Immigration Museum’s new group of exhibits offer visitors a chance to engage with tattoo on a level deeper than skin. Here, stories of culture, tradition and migration speak through embedded ink.

Without personally experiencing a tattoo, it may be hard to understand why somebody would undergo the painful procedure. For example, Joseph Banks, the 18th century naturalist on board Cook’s first voyages, was quite taken aback at the tattooing process of a Samoan girl:

“What can be sufficient inducement to suffer so much pain is difficult to say; not one Indian (tho I have asked hundreds) would ever give me the least reason for it; possibly superstition may have something to do with it, nothing else in my opinion could be a sufficient cause for so apparently absurd a custom”.[1]

Banks, like so many of his Age, disregarded the ritual as quaint – a primitive custom in need of Enlightenment. Perhaps he had not yet been exposed to Europe’s rich and ancient tattoo history – notwithstanding it was episodic, diffuse and nonlinear in nature. To use Alfred Gell’s term, European tattoo had hitherto floated “unanchored” to any codified and universal meaning, methodology, or vernacular, and was referred to mostly as “scratching” and “pricking”.

Missionaries and colonists thusly sought to discontinue the ‘savage’ practice, all but effacing it from the Islands – not, however, before piquing the interest of sailors. According to Jane Caplan’s edited volume, Written on the Body, upon returning home seamen helped propel the craft into a new level of visibility. Through aesthetic and appellation (the Tahitian word tatau, meaning to mark or strike, was adopted and later translated to tattoo), they inserted it into the collective consciousness of modern Europeans.

Paul Stillen, Annie, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Lekhena Porter

Today, divided across three stately levels, Our Bodies, Our Voices, Our Marks, explores the contemporary form of Polynesia’s ancient and embedded tatau alongside the equally potent tattoo tradition of Japanese irezumi. Complimenting the two photography exhibits are four installations – curated by Stanislava Pinchuk – that offer a view of tattoo beyond the limitations of tradition.

Paul Stillen, Group, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Lekhena Porter

Visitors are greeted by her curation of six photographed tattooed bodies featuring the work of Melbourne based tattoo artist, Paul Stillen. Connected Bodies explores the relationship he develops with clients as they collaborate to create tattoos that pay homage to the wearer’s diverse cultural heritage. It is an insight into a creative process that outsiders to the craft may never consider, yet, the exchange between tattooist and client can be one of mutual palpable vulnerability, where the artist strives to materialise what can often be hidden deep within a client’s psyche. Whether consciously or not, Stillen’s botanical tattoos resemble Sydney Parkinson’s water-colour drawings of native Australian plants made during Cook’s first voyage. That symbolic irony pulls into focus the land on which the museum stands, and the devastating effect of immigration on First Peoples.

Paul Stillen, Chrystal, 2019. Photograph courtesy of Lekhena Porter.

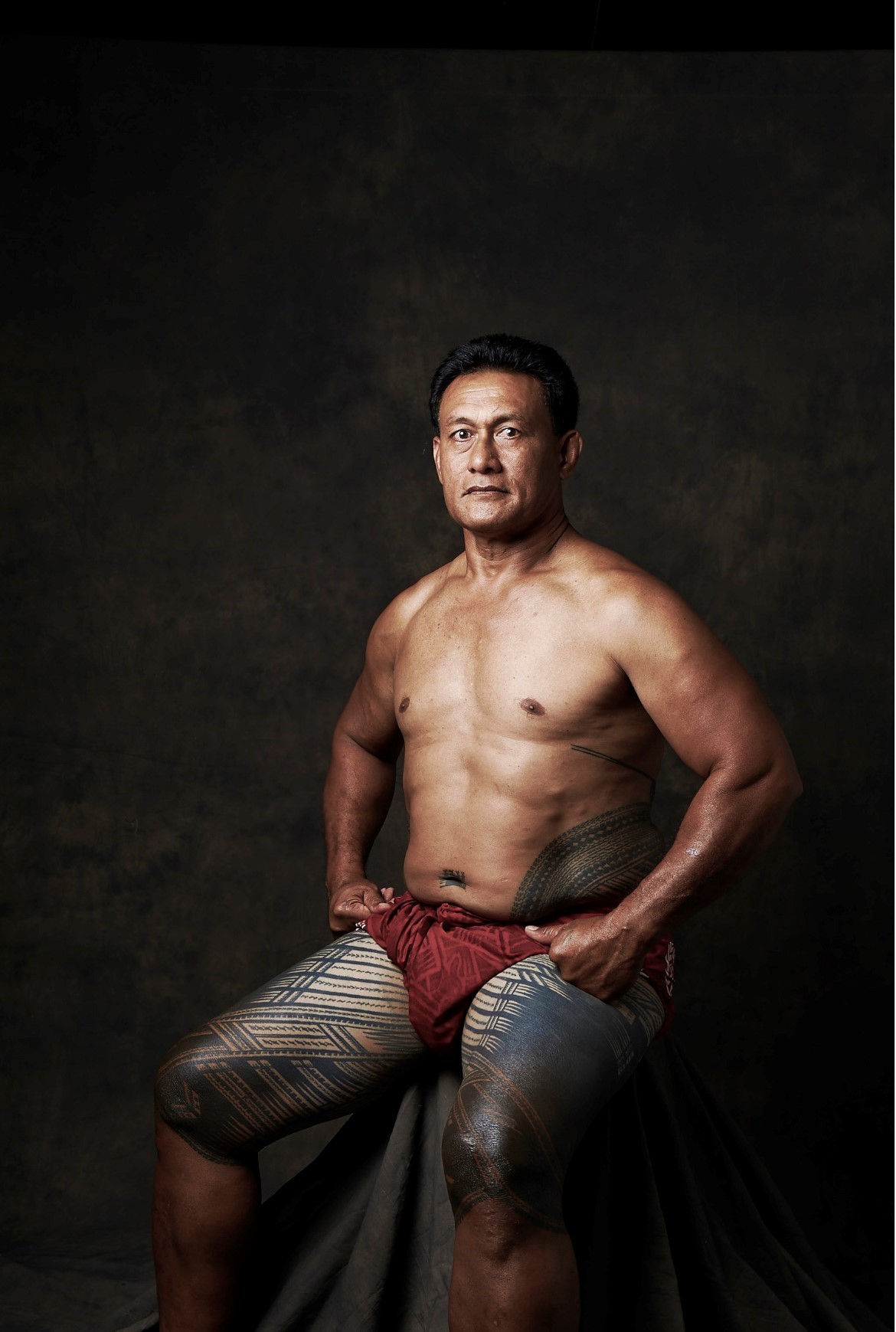

On the first level Tatau: Marks of Polynesia examines the ancient custom of Samoan pe’a (traditional male tattoo) and malu (traditional female tattoo), providing insight into how they form a complex body of rituals and motifs inextricably linked with transitions to adulthood, culture, and sacredness.

The exhibition explores the emergent contemporary Polynesian style that embodies concepts of both pe’a and malu. Its vibrancy and visibility are due in part to the global migration of Polynesians, outsider appreciation of the style, and, not least, the efforts of the Sulu-ape family, one of Samoa’s oldest and most revered custodians of the sacred practice. The process of attaining a pe’a in a traditional manner lasts up to five consecutive days, the physical and psychological punishment of which cannot be expressed in words, although, a Samoan friend once relayed to me: “it was my PhD.”

Notably, Polynesian tatau – heavy black work and the absence of pictorial iconography – was instrumental to the expansion of tattoo art. The pioneering American publication Tattootime featured the powerful black graphic work in their 1983 issue, New Tribalism. Its publication gave birth to the “tribal” style tattoo and swiftly became dominant amongst tattooists and clients.

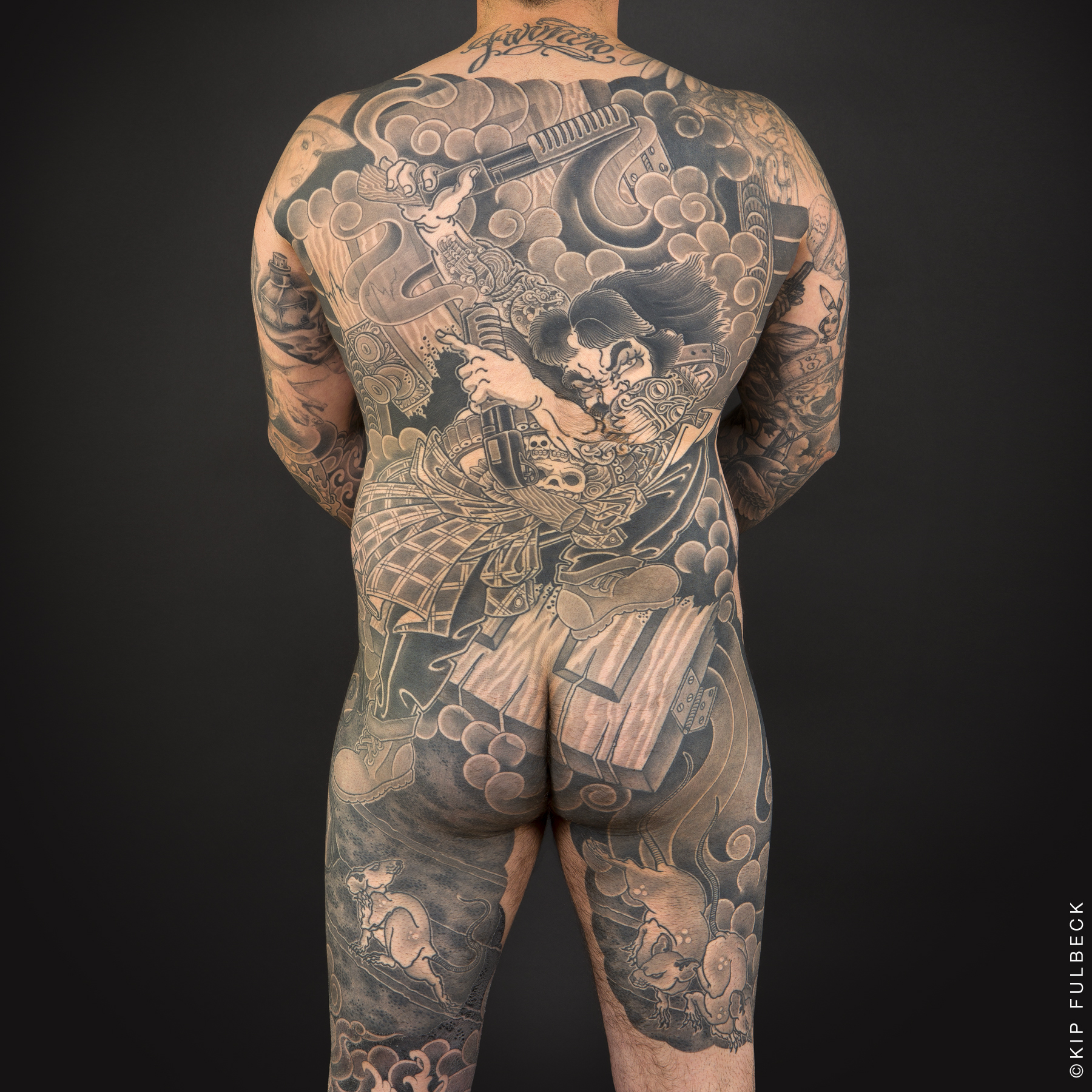

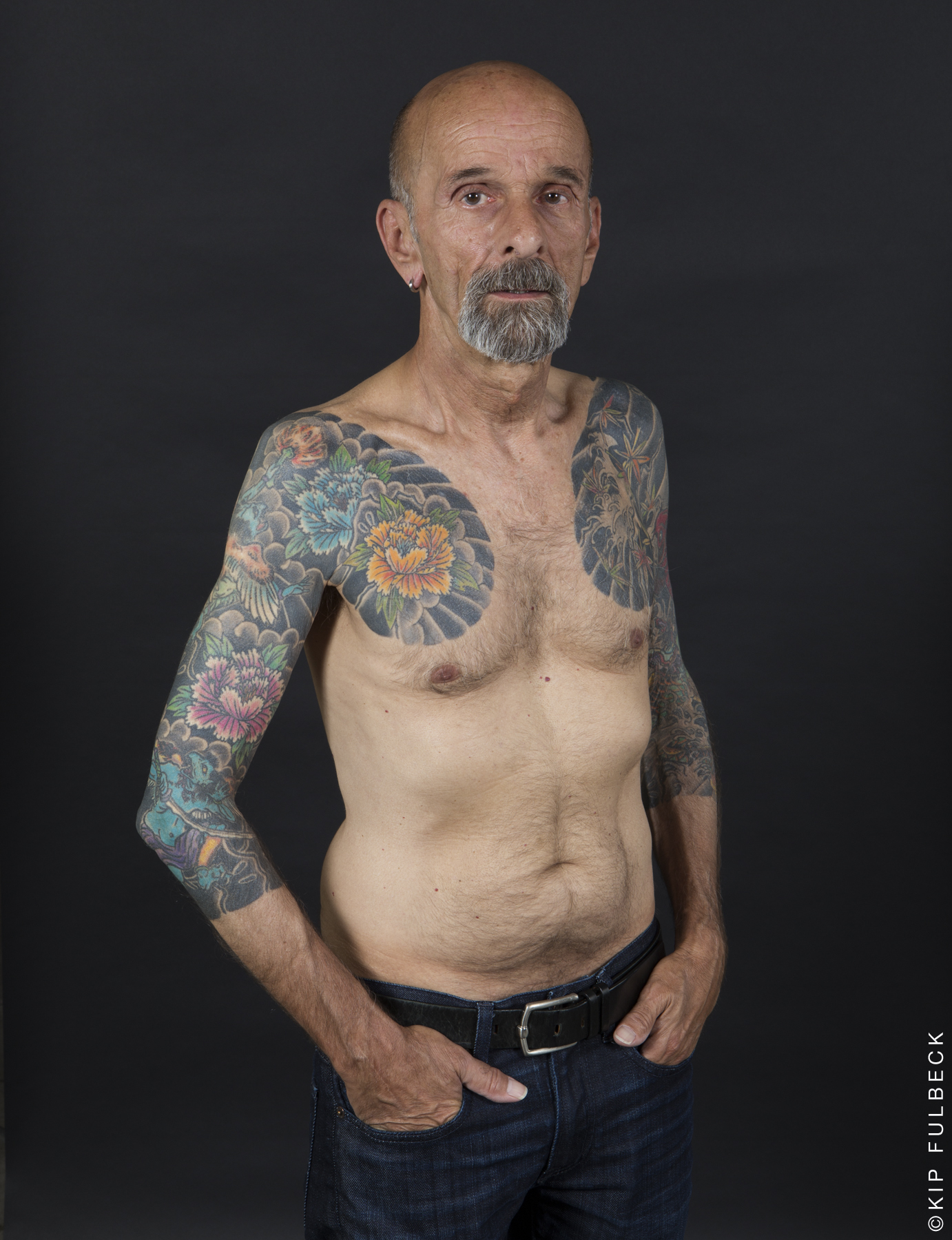

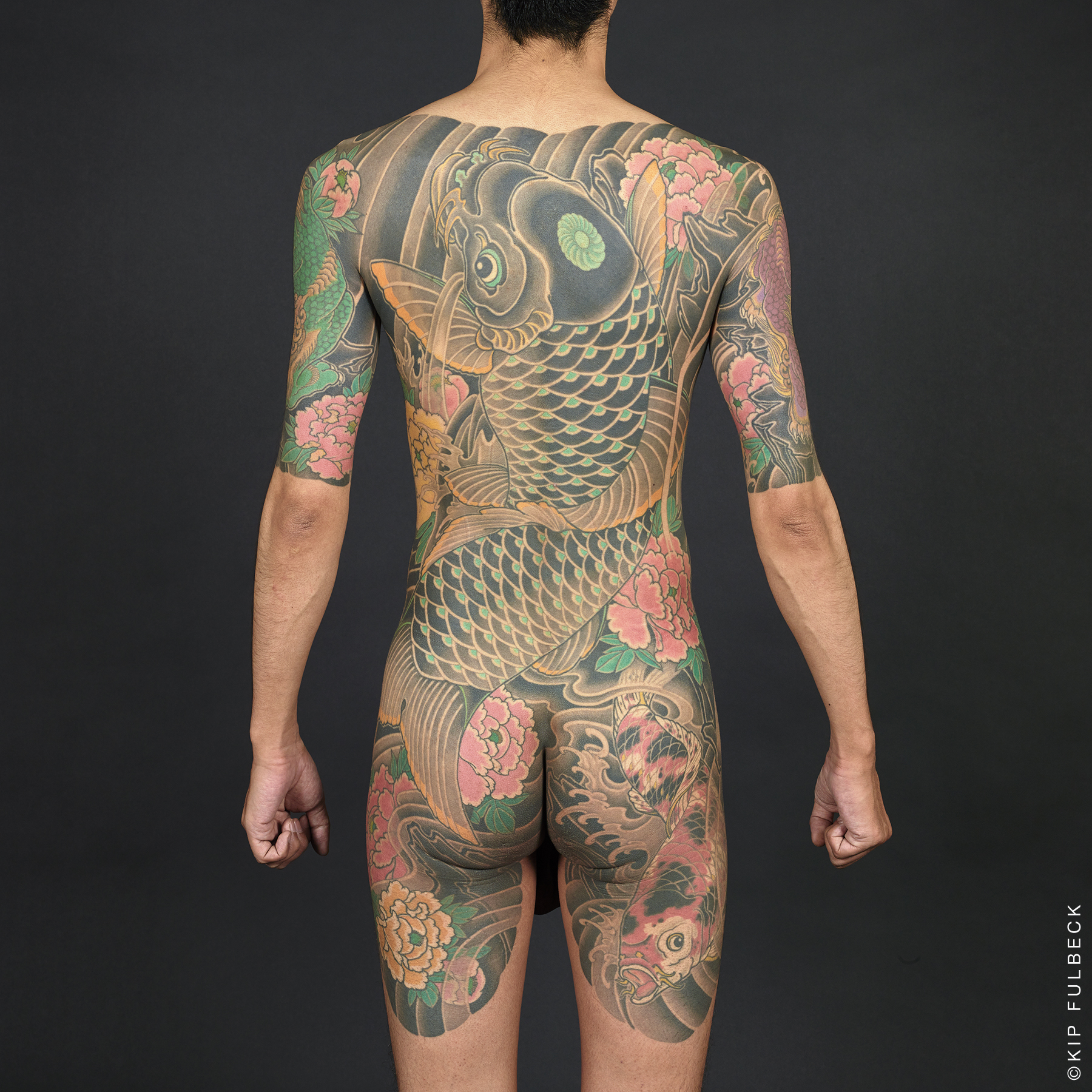

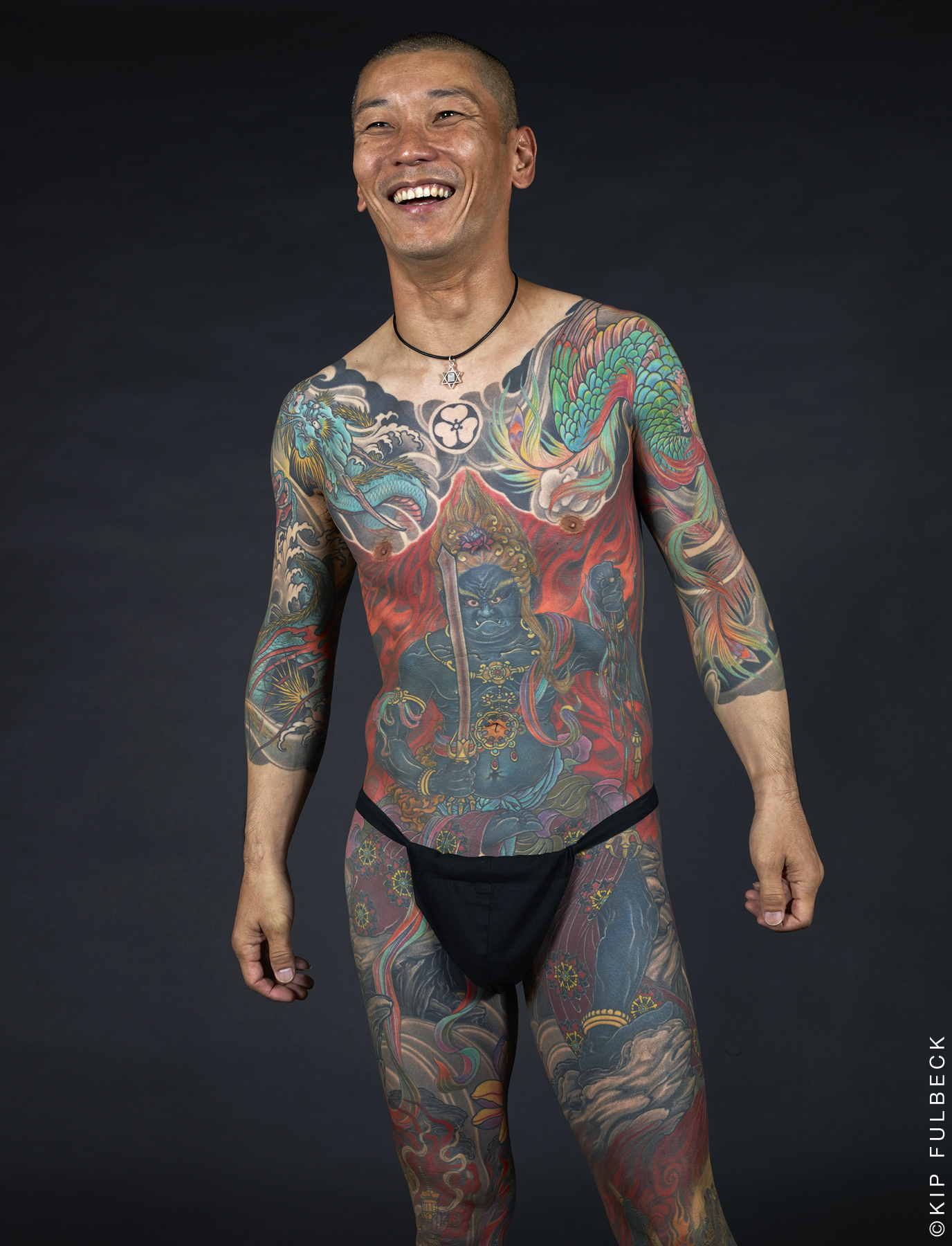

Indeed, the third floor is where, arguably, tattoo culture’s most distinct and recognisable style is found, one that helped elevate western tattoo into the artform we see today. Formed through a complex history, Perseverance: Japanese Tattoo Tradition in a Modern World explores contemporary Japanese decorative tattooing. Curated by Takahiro Kitamura, the exhibition features the work of seven pioneers and legends, where the intricacies of regional and tutelage differences can be seen in the pores of their work.

As a product of the Edo period, its iconography and symbolism were developed from the popular arts of ukiyo-e (woodblock prints). Irezumi peaked in popularity around 1872 but the Meiji Restoration saw Japan’s new government ban the practice. In a bid to present an image concurrent with other modern, industrialised nations, the law only served to increase its mystique by driving it underground, Here, the government has continued –with varying degrees of success – to legislate downward pressure.

While Polynesian and Japanese tattoo are steeped in tradition both aesthetically and in execution, Pinchuk’s own tattoo work represent its antithesis. It is diminutive, delicate, and rudimentary, without codified meaning and administered by someone for whom tattoo is not a primary medium.

The contrast isolates the core of what makes tattoo, in my opinion, so magical, timeless, and powerful: whether in your backyard, home or studio, regardless of who you are, your corporeal artefact can be received, given, and laden with any sentimental, talismanic, social, cultural or political meaning you wish to ascribe it, even amongst the “carnival of signs”, so to speak.

Our Bodies, Our Voices, Our Marks is at once an essential tattoo art exhibition and visual exploration of how culture and meaning can follow the movement of marked bodies across both space and time.

[1] Banks, ‘Manners and customs of S. Sea Islands’, August 1769, printed in The ‘Endeavour’ Journal of Joseph Banks, ed. J.C. Beaglehole (Sydney, 1963), vol. I, p. 336.