Portraits of South Africa's Bloodiest Prison Gang: The Number

On face value, their prison tattoos look like what you’d expect from crudely sharpened guitar strings and burnt rubber. But for those in the know, the motifs offer a rare glimpse into the inner workings of The Number, a South African prison gang with a violently enforced code of silence.

With a history purportedly stretching back into the late 1800s, The Number is one of the world's oldest gangs, maintained with an intricately complex hierarchy that spans across three factions—the 26s, 27s, and 28s. The 26s import currency, tobacco, and drugs into the prison; the 27s uphold the law, making them the most feared; while the 28s defend prisoner rights.

Photojournalist Luke Daniel used his friendship with one high-ranking insider to photograph members and their tattoos. He spent two years on the project, entitled ‘Tjappies Van Die Point’, documenting what he sees as a uniquely African subculture. No one has done this before, and we were keen to hear how Luke got such intimate access, what he learned, and what it was like hanging out with some of the country’s most ruthless criminals.

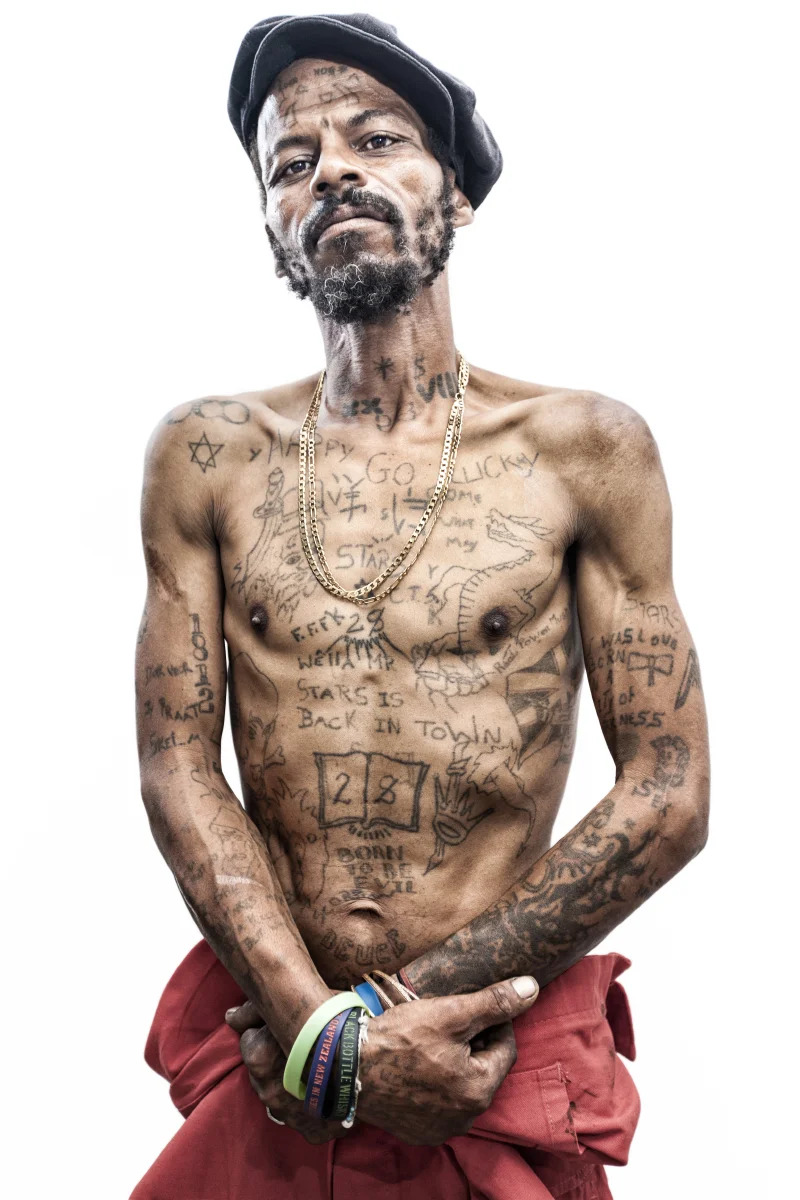

Gerald 'Horings' Hugo

Firstly, what does Tjappies Van Die Point mean?

Tjappies Van Die Point literally means Tattoos From Prison.

Tjappies is a colloquial South African term used to describe tattoos, specifically those rudimentary in aesthetic that, more often than not, were completed in prison. It originates from an old brand of South African bubblegum—Chappies. The wrappers contain interesting ‘did you know’ facts. So, the term became associated with prison tattoos because the markings etched into skin often reveal facts about the wearer—crimes committed, gang affiliation, and more.

So how did this project begin?

Well, I became interested in tattoos at a young age. I hung out and helped out a few dodgy shops on the 'bad side' of town. So, my introduction to tattooing was always tinged with a criminal element, and I was always fascinated by prison tattoos—the simplicity, the ingenuity, the craftsmanship.

I’ve always been interested in tattoos in the context of rejecting societal norms. Now, tattoos have become fashionable, but there are still markings which are still taboo.

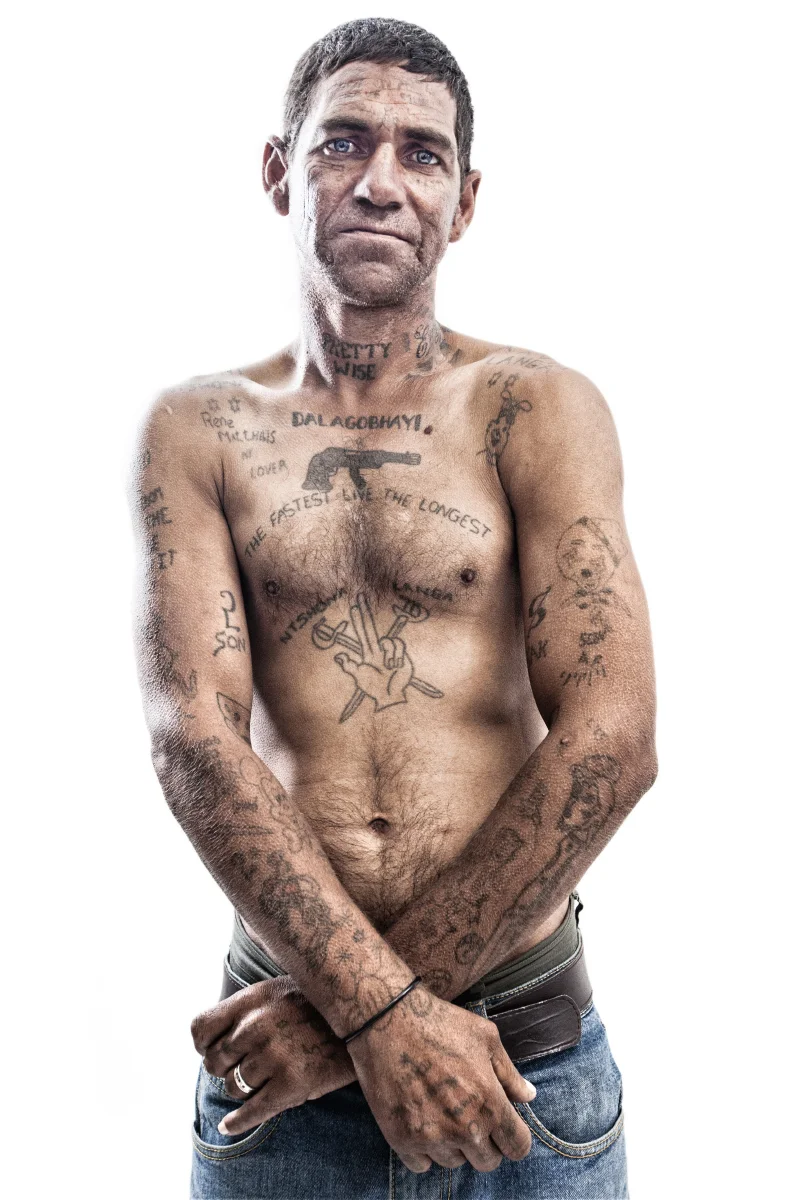

Punzo

Prison tattoos, especially within the South African context, are still a purposeful rejection of ‘normal society’. The tattoos are easily identifiable as being done in prison and often contain violent and obscene motifs which adorn faces and hands. These tattoos are still symbols of the outlaw, and wearing them comes at a great cost. Add in the mythology of The Number Gang, which has ruled the South African prison system for the last century, and how that tale is told through the permanent etchings is storytelling at its most pure and dangerous.

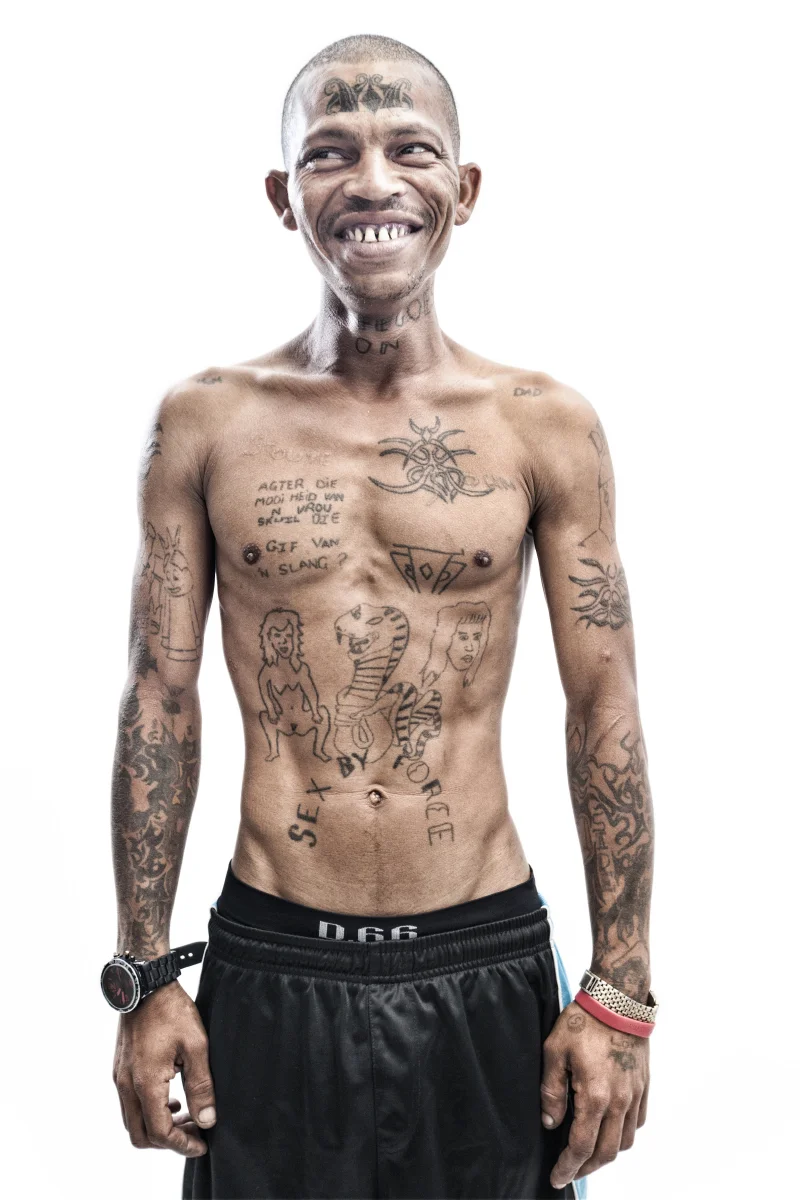

Erefaan

I chose to document these prison tattoos because of their uniquely South African aesthetic, but, as the project went on, it became more about the process of tattooing in prison, the motifs represented, and the societal isolation and discrimination experienced by heavily tattooed convicts. The struggles of reintegration into communities, once released from prison, became all too clear.

In reality, the project was a way for me to deepen my own understanding of South African prison tattoos and the power behind them.

How do you go about recruiting subjects?

I was fortunate enough to spend a lot of time with a high-ranking gang member who had spent over 20 years in prison. We became friends; he was trying to get back on his feet after serving serious time but his tattoos had made it hard for him to get a job or reintegrate back into his community. So that got my mind working and I hired him as a ‘talent scout’ of sorts, to help bring the project together by finding people in similar situations.

Every single person I photographed was, or still is, active in gang activity—both within prison, as a part of the Number Gang (you don’t ever really leave the Number), and on the outside as part of some infamous street gangs. Towards the end of the project I was getting calls from gangsters saying “hey, I hear you’re photographing tattooed prisoners – take my photo!”.

Hangpaal

Tell me about the Number Gang, how did they come about, who are they and what are they like?

Truthfully, I’m not at liberty to discuss the Number Gang in great detail. The information is available out there, and there are more than a few ‘outsiders’ who would be willing to spill the beans on The Number.

The greatest thing about The Number, though, is its rich mythology and folklore which has remained largely confined to those belonging to the gang, who, in theory, took an oath to keep the gang’s dealings a secret. Obviously, these secrets have been divulged over the years. If you’d like to find out more about the Number Gang I recommend reading Jonny Steinberg’s The Number. What I will say is that The Number has by far the most intricate and involved backstory of any other prison gang I’ve ever heard of. The history and heritage of The Number stretches back hundreds of years, to a time when young black men were forced to abandon their rural villages in search of work on the mines in central South Africa and Delagoa Bay (now Maputo, Mozambique).

John

How are they positioned in general Cape Town society?

The Number gang was historically limited to prison—meaning that street gangs ruled the ‘outside’ world and The Number was the omnipotent force behind bars. That all changed in the late 1980’s when Cape Flats drug dealers started making heaps of cash through the mandrax trade.

Essentially, the leaders of street gangs then ‘bought’ their way into The Number once incarcerated; in order to bypass the gruesome rite of passage required to join. For a fee, gang leaders from the outside world became ‘safe’ in prison, without having to do much dirty work.

Though, in turn, this upset the balance of things—with The Number spilling out into the ‘free world’ by forming solid relationships with street gangs. Simply, the drug lords had the money on the outside, and The Number had the power on the inside. Drug lords promised Number gang members work on the outside upon their release and this led to a massive explosion of violence on the Cape Flats, something which still persists today, arguably, worse than ever before.

Mandown

Can you tell me about some of the members you’ve befriended?

Gerald ‘Horings’, my friend and fixer, is without doubt the most outstanding subject and person. He parks cars and collects scrap metal to make ends meet. As is the case with most of the people I photographed for this project, they’re not inherently bad people—just people born into abject poverty who suffered extreme trauma and abuse and ended up making some seriously bad decisions which cost them their lives and brought pain and misery to their own families and the victims of their crimes.

Most people I photographed were arrested and convicted of violent crimes—murders and assaults. In prison, as part of The Number’s initiation rites, they committed further violent acts against other prisoners and warders. Some prisoners, who were sentenced to a few years in jail, ended up spending 30 years behind bars for their commitment to The Number.

One guy, who calls himself ‘Mandown’, stole a loaf of bread in 1978 and got put into a cell with some high ranking Numbers. He got inducted and, due to further crimes committed while incarcerated, ended up being released in 2003.

Every single story told is one of heartache, violence and momentary madness.

Owen

What kind of equipment would they use to tattoo?

A sharpened guitar string usually serves as the needle. Burnt rubber, turned to ash and mixed with water to form a paste, serves as ink. All prison tattoos, until very recently, were all done by hand – no machines.

Can you explain the different symbology, iconography and meanings you discovered throughout their tattoo motifs?

Well, without going into too much detail about the inner workings of The Number, there are fundamental elements of the gang that are important to understand within the context of the markings.

The 26’s are tasked with gaining currency inside the prison, either through money or contraband, drugs, tobacco, that sort of thing. They’re master smugglers and manipulators. They’re said to work from sunrise—hence the term ‘sonop’ (sunrise) being a common greeting and motif present in the tattoos. Pumalanga, the Zulu word for sunrise, is also used.

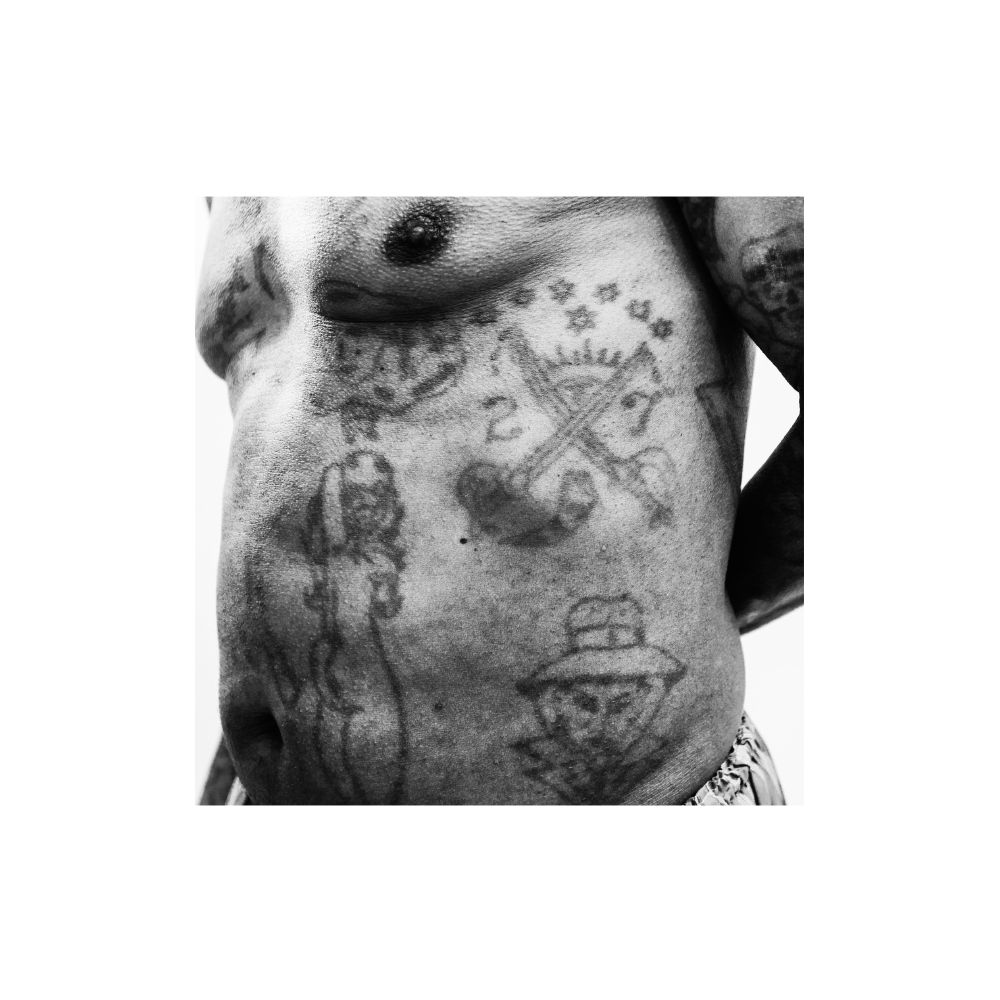

Close-up of Hangpaal’s Tattoos

The 27’s are tasked with upholding the law of The Number and are the most feared and dedicated gang members. Their motifs often include weaponry, crossed cutlasses, and verses relating to the rule of law within The Number.

The 28’s are, traditionally, tasked with defending prisoner rights, usually through force, such as attacking prison officials should The Number not receive adequate attention and respect from authorities. They also dominate underlings, and non-gang members, by the use of sexual force, i.e. sodomy. Motifs including obscene sexual scenes and penises are common. In contrast to the 26’s, they work at night, and tattoos often relate to ‘sonsak’ or ‘Shonalanga’, Afrikaans and Zulu for sunrise, respectively.

Close-up of Desmond’s Tattoos

What stood out to me is the juxtaposition involving hardened criminals and comical cartoon motifs. Despite some of the people I photographed having committed heinous crimes, many of them had joyful cartoon characters tattooed on their bodies. This is because, I’m told, comic strips in prison formed the basis for many ‘stencils’; in other words, very often imagery available to prisoners was limited to cartoons found in newspapers.

Another thing which fascinated me was the presence of script-heavy tattoos. Some guys had their whole backs filled in writing—hundreds of words—most in broken English, despite most of the wearers and tattooers being Afrikaans. The essays inked into their bodies tell stories of life’s hardships, gang folklore, and self-inflicted isolation from normal society.

Close-up of Punzo’s Tattoos

And any outstanding tattoos?

The penis tattoos worn by the 28’s are iconic in their own right. Cartoon characters juxtaposed alongside rape and murder scenes are interesting, in a repulsive kind of way.

The tattoo which is most important to me is a phrase I was ‘gifted’ by Gerald ‘Horings’, which reads “Go tell it to the birds”. It’s the most meaningful to me—I got it tattooed on my neck.

The tattoos are intrinsically linked to the personalities of the people that wear them, but relate more to the crimes committed, and time served as a result, more than a defining overarching theme of their entire lives, dreams or aspirations.

Pieter

In South African prisons, as I’m quite sure is the case in most jails all over the world, prisoners get tattooed, heavily tattooed, to appear more intimidating and to further reject societal norms. Face tattoos baring obscene phrases are common—this is a complex blend between ego and self-destruction. It’s these kinds of tattoos which will earn respect and notoriety behind bars but damage the person’s chances of ever successfully reintegrating back into society. Nobody wants to hire somebody with ‘fuck you’ inked into their forehead—but in prison, that kind of anti-establishment, nihilistic attitude is appreciated.

Most of the people I photographed are proud of their tattoos, despite the pain and trauma contained within the markings as reminders of a dark past. In many cases, the tattoos are regarded as battle scars.