Born criminal: How crime reunited John Richard Birkby with his biological family

The 19th century social scientist and founder of criminology Cesare Lombroso posited that criminality was biologically inherited. He believed latent criminals could be identified by specific physiognomical traits such as protruding ears, sloping foreheads, or excessively long arms—”primatial characteristics”.

Theories of socialisation would come to challenge Lombroso’s view. Here, crime is understood as a response to one’s social environment—their upbringing and social environment. The distinction between these theories forms the basis of the common dichotomy known as ‘nature versus nurture’.

So, what happens when the baby of a career criminal is adopted into the household of a pious and nurturing family?

It’s a question inspired by my friend, Sam’s father (pseudonym). He would often reveal titbits of his father’s life story to me: founding member of New Zealand’s notorious Magog’s Motorcycle Gang, prolific drug smuggler, convicted armed-robber—chrome hook in replacement of his hand. But the most outlandish vignette revolved around a letter his dad received while in prison. So when Sam’s dad visited Melbourne I jumped at the opportunity (with some hesitation by Sam, “just remember, he’s old school”) to hear it first-hand.

This is the story of John Richard Birkby, and of nature finding nurture.

§

~ Prologue ~

At 19 years of age John Richard Birkby finds himself sentenced to 7 years in New Zealand’s toughest prison, Paremoremo. The facility is relatively new and houses some of the country’s most violent criminals. Birkby is the youngest inmate and is guilty of assault at knife-point.

He has been married for several years but soon after the hearing that lands him jail his 17-year-old wife files for divorce. It is 1976, Birkby is scared, Robert Muldoon is Prime Minister, and the nation's first McDonald's restaurant opens in central Porirua.

Birkby is quick to adapt to prison. He accepts the flow and floats accordingly. The other young inmates struggle, but to him “it feels like second nature”. His temperament and character do not change. Big inmates do not intimidate him.

He realises that he feels more at home with hardened criminals than with his parents.

Several months into his sentence he receives a letter from Auckland. It is from a woman, Dear John, it begins, I am a close relative, I would like to come and visit you. But Birkby has no relatives in Auckland.

who the fuck is this? he thinks.

A visitor’s pass is sent out.

Several days later as Birkby sits in an empty hall reserved for haste exchanges, reunions, apologies, reassurances and promises. The doors swing open against a phalanx of familiar strangers. From their epicentre a woman emerges.

“I guess ya wondering who I am,” she says smiling.

“Well I’ve got a fair idea,” Birkby responds, having immediately noted their identical proboscis.

“I’m ya mother. These are ya brothers and sisters. Actually, you have another brother but, he’s in jail too. This jail.”

I finally found me family, he thinks.

§

Part 1: Genes

It is the 1950s and the prevailing view of New Zealand’s government is children are best raised in a two-parent family. An adoption act legislates the complete split between birth mother and adoptive family. Single or divorced mothers are labelled selfish if they refuse to give up their child to childless married couples for adoption. The process is shrouded in secrecy. Most will never see their babies again.

Birkby remembers very clearly the day his mother told him he is adopted. He is 13, playing on the back porch of his middle-class New Plymouth home.

“John, I’ve got something to tell you.”

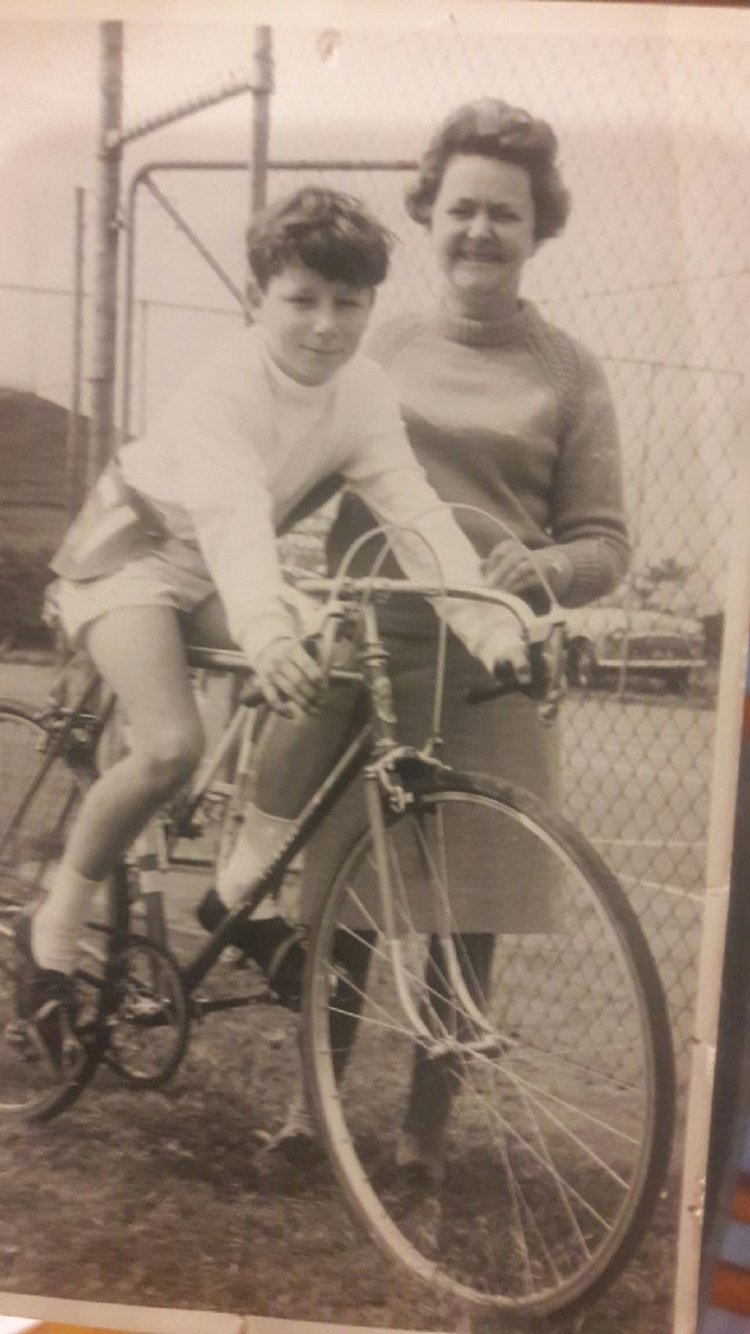

Birkby and his adoptive mother

She tells him he comes from a big family. She tells him her and Les, both committed Baptists and diligent community members, are his adoptive parents. Birkby listens but the words do not sink in. Instead, they encase him like armour. She continues, telling him they wanted to adopt a son to carry on the family business.

not because you loved me? he thinks.

Birkby feels deceived, that must be why Les never takes me camping, he thinks.

He asks about the big family—the real one. They were no good, he is told, the mother was immoral and father a drunk, their sons in and out of jail. John was lucky, he is told, he was given a second chance at life.

I have brothers? He thinks.

But to Birkby this feels like a third chance at life. Anything bad he did from now is justified because he supposedly comes from a family of yahoos.

Genetics dictate behaviour—it’s in me genes, he thinks, and that’s not Levi’s.

***

Birkby’s first crime is several months later.

It’s midnight and he meets with some neighbourhood kids.

“Let’s steal a car,” someone proffers.

They steal a mini. There are four of them—all called John. They smash the shit out of the car, laughing the whole crime through. Birkby feels good, he was wearing his new genes and they fit snug as a bug.

A John suggests they sink the diminutive vehicle. Another John drives toward the wharf. Three Johns holler in the back, cajoling each other into admitting fear and homosexuality. They drive it off the boat ramp. It won’t sink.

Birkby late teens

Johns sit at the end of the harbour watching it bob up and down like a buoy, its indicators still blinking hopelessly. Blink blink, blink blink, blink blink.

sink ya fucker, sink! Birkby thinks. Eventually it does sink. But a woman breastfeeding at her front window identified two of the Johns, including Birkby.

***

The only time Les has anything to do with his adopted son is as disciplinarian. But every time the belt comes off, Birkby’s new genes tighten. He imagines what his real family were doing—especially his brothers.

fuck this shit, he thinks, and vows from then to only be on the giving end of beatings.

§

Part 2: Magogs

It is the early 70s. Birkby is 15, dressed in bell bottoms, Gary glitter shoes, a calico top, and long hair—nobody can fuck with him now. He leaves home and moves downtown.

At first it’s a few punch ups. They aren’t hard to start, Birkby is short—his temper shorter. He earns the nickname shotgun because they’re the same height—and he uses one to bash cunts.

He roams with a group of guys, drinking, fighting, fucking, and riding. One night, members of Upper Hut’s Sinn Fein gang enter New Plymouth to drink. They leave the same night bloodied, beaten, and with a vendetta.

oh well let’s start a club then, the donnybrook’s victors think.

It’s 1974 and the Magog Motorcycle Club is established. They’re 1 percenters. And although they’re all white, if anyone fucks with the club—white, black, brown, blue, or purple—they’ll get what’s coming to them.

Birkby

The Magogs have the townspeople’s support as sentinels, alerting the club when rival gangs like Black Power and Mongrel Mob arrive in town. Enforcers are sent and bodies are left bleeding to death on city streets.

The police deliberately stall—it is easier to deal with one group of tired victors than two groups of belligerent assailants.

The Magog’s frequent savage punch ups establish a name for the club. Life is party all night, drink piss, smoke dope, ride bikes. Birkby is equal parts jovial and antagonistic, I love a good laugh—at the expense of others.

He lives for the intoxicated moment, committing crimes without considering consequences. He gives no thought to what could happen if he is caught. He feels invincible. Entitled. The prospect of jail does not temper his impulsive hard-boiled nature.

Birkby

He just thinks, look, I’ll cross that fence when I come to it.

Two years later at 19 years of age he commits a violent assault at knife-point.

***

Something catches the corner of Dolce’s eye. A small headline—Seven years’ jail for lawless man, John Richard Birkby. Looking up at her is the aged monochrome face of her seventh child, the one she was encouraged to give up. The one she last saw over two decades ago. She puts pen to paper.

***

“I’ve got this strange letter from this lady here.”

Birkby’s cellmate, Hell’s Angel, Neil Underwood, looks up from his bunk.

“What’s it say?”

“She wants to come visit me.”

“Who’s it from?”

“Dolcy Couldran.”

“I know that family.”

“Bullshit.”

“Yeah, when I first looked at you I thought you was one of them!” says Underwood.

oh yeah, thinks Birkby. The penny drops, fuck, he thinks, maybe this is my real family.

***

that’s me mum!

The moment Dolce walks through the prison visiting room doors is etched into Birkby’s mind. They sit, surrounded by brothers and sisters, and talk the visiting hours away. Dolce comes back every weekend throughout her son’s sentence to talk more.

His adoptive parents are devastated at the crime—they visit him twice a year. But Birkby appreciates this, and reassures his adoptive mother with filial love. But he wants to get to know these other people too, the ones that look like him.

Dolce tells Birkby about William, his father—a real bad bastard. About how when John is born William turns up to the hospital drunk and gives chocolates to the young nurse. He is thrown out of the hospital as John enters it.

There were money problems. There was no food in the house. She had black eyes, broken ribs, and defied gravity through windowpanes. The doctor strongly suggested she part with John.

Nearly all his four brothers and seven sisters are jailbirds. One is associated with the Hells Angels, another the Grim Reapers, another the Sixty Ones. One sister is a stripper, another a hooker.

that’s why I like bikes! He buzzes, it’s in my system!

It sounded to him like the only one who hadn’t been in jail was his mum. He realises he was never wearing his genes. He was his genes, and he had no control over it. He did it because it is what he is.

And sitting in the Wing Birkby listens to his brother Larry in Classification and realises genes are the same reason Larry did what he did. He explains through the slide how the gun he sold the Hell’s Angels was used in a murder. They chat for about half an hour, both bewildered at the circumstances of their family reunion.

After serving 6 years Birkby is released. He is 25.

§

Part 3: The Pink Pussy Cat

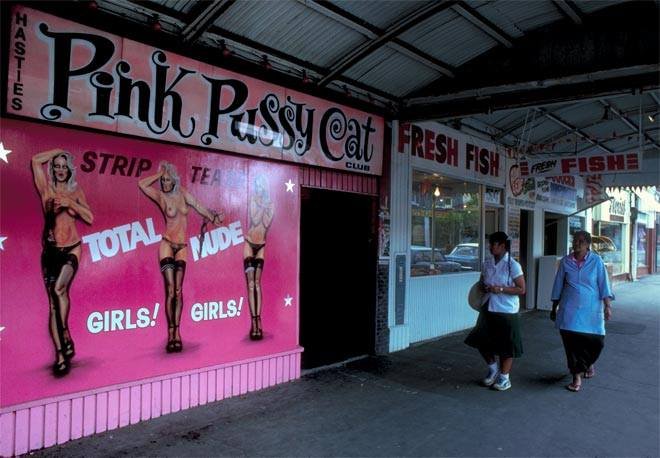

Hasties Pink Pussy Cat

It’s 1963 and Rainton Hastie invests £60 to open New Zealand’s first dedicated strip club. Notwithstanding death threats, firebombs, and the ire of Women Against Pornography, the Pink Pussy Cat becomes synonymous with Auckland’s growing sex industry. Hastie contributes further with two additional ventures, the Velvet Touch and Pleasure Palace massage parlours.

After two decades frequent run-ins with the law and an oversaturation of Auckland’s parlours are putting pressure on the industry’s profitability. Hastie, known now as the ‘King of the g-string’, sits quietly with staff to contemplate the future of his small empire. Sitting opposite him is the Pink Pussy Cat’s new manager, John Richard Birkby.

The job, along with board above the Pleasure Palace, is obtained at the behest of Hastie’s girlfriend Sharon—one of Bikby’s genetic sisters. The working girls—sisters included—like Birkby. The ex-con is an entertaining raconteur. Shouting over Billy Idol’s Hot in the City, Birkby energetically prognosticates at Hastie.

“This is my concept of woman, right. You meet them, it’s a physical attraction, it’s an animal attraction, you wanna get into each other’s pants and have a good time. You get into the sack and it’s like oh yeah she’s good that’s great but after one month two month she wears her socks to bed or takes her teeth out and this is the turning point where you decide ‘do I want to be with this person’? Sometimes you think well I can deal with that this is okay and the next thing you know it’s ‘oh you need to come to mum’s’ and they want you to do what they’re fucking doing all the time. A relationship is a partnership, it’s you both put in and you both take out, but when one wants to take more than the other, na, fuck off. And they always try to change ya and make you do things you don’t want to do you know. Next thing you know you’re this wimpy little fucking ‘yes dear no dear’. And then—they don’t give ya sex. Well, they can get fucked because I don’t ask much from a relationship, and when I say much I mean I just want the perfect little house and the perfect little wife that sits at home and cooks food and whatever—you know?”

“Oh yeah, and how would you be the perfect husband?” Hasite asks dismissively.

“Oh well I’d come home and root her.”

Several months later Birkby remarries and moves to New Plymouth where he fathers two children.

§

Part 4: Chrome

Birkby works hard as a welder but again he gravitates to crime. Married life is dull, and his partner Meagan wears her socks to bed. By the 1990s he is making regular trips between New Plymouth and Auckland trafficking cocaine and LSD. Once again life is party all night, drink, take drugs, and ride bikes.

it’s amazing how many friends you get when you’ve got cocaine and LSD, he thinks.

Birkby

After one such trip he is drinking heavily with an associate at the Masonic Tavern. They mount his Harley—Birkby riding pillion—and twists the throttle around a sharp bend. Birkby slides with the bike as it comes to a hard halt at the obstinance of a grass bank.

His neck snaps. So does his arm. The smell of flesh and sound of flames suffocate him into a coma.

Every time his eyes open a foreign name greets him from the wall: John Richard Birkby. The nurse offers him the finer details: bike accident; two months ago; 45 percent burnt; died twice; strong will to live; amputated hand.

amputated Hand? He thinks.

The doctors reassure him of advancements in prosthetics. He is given a demonstration of the ersatz extremity—its life-like flexibility and spindly faux digits repulse him. Not a believer in imitations Birkby opts for the quintessential accoutrement of a 1 percenter.

A chrome hook.

***

The Omnopon prescribed for pain leaves Birkby with a severe drug habit. For nearly two years he imbibes the profits of his illicit road trips. The cocaine is effective at numbing the senses—physical and psychological.

While running goods up the West coast Birkby ruminates about his history and heritage. He thinks about his father, William Couldran—and how he also spent time in jail. He thinks about his adoptive father Les—the beatings and aloofness. He thinks about his own future, his two boys, his legacy.

Up north a new buyer elicits caution from Birkby’s colleagues. They run tax checks on the buyer’s details. The name appears three times: one candidate is overseas, another too old, the last is care of Motueka Police Station.

oh hello, he thinks, and concocts a plan befitting Scarface in both grandiosity and delusion—blow off the undercover cop’s kneecaps and keep the money.

He takes the $90,000 worth of product to an Auckland motel room and sets a time with the “buyer”. Birkby takes a friend and with sawn off shotguns at their side they party in the lodgings.

“Oh well and how would you be the perfect husband then?” The friend eagerly asks after Birkby finishes regaling with his diatribe.

“I’d come home and root her—I never met a girl that didn’t like a good stumping.” The adapted version evokes rapturous laughter.

They fall asleep.

At 3am Birkby is roused by the cold barrel of a .38 pressed against his head.

“ARE YOU JOHN RICHARD BIRKBY!” shouts its handler.

“Yeah yeah.”

“PUT YOUR HANDS UP!”

“I’ve only got one!”

“DON’T GET FUCKING SMART!”

***

Birkby is awarded bail. Out of pocket and in need of some quick cash for gear he acts upon a rumour. The local Lotto shop is said to have 15K in the safe. He robs it, with a sawn-off shotgun.

$250 and a few hours later the Armed Defenders Squad are kicking in the doors of usual suspects. The next morning Birkby gets wind of the hunt and offers himself up, not before negotiating the terms of his 5pm surrender—spending an uninterrupted day with his two boys. After a late afternoon beer, he exchanges goodbyes with friends and family and strolls into New Plymouth Central Police Station.

Birkby’s first day on remand is his first day sober in nearly two years. His body goes into shock. He shivers as the sun hits the back of his neck outside court and for the first time realises he has a habit. He is sentenced to 11 years, 7 for the LSD and 4 for the armed robbery.

In Mt Eden prison many of the old fixtures note the resemblance between Birkby and an earlier inmate, William Couldran. Birkby’s old man was a boobhead, they tell him, even the screws knew him well.

well I guess that’s what I got from me dad, he thinks—jail.

This lineage bodes well for Birkby—he is well looked after. But this sentence is different. He has two boys, they visit regularly.

right, he thinks, I’ve gotta sort myself out.

Birkby enrols in Mt Eden’s pathways program. He is studious and gains a degree in social work. He likes the idea of helping people, especially ugly bastards like the ones in here. Because he knows what it’s like to be judged by appearances—a hook tends to invite nothing less than furtive avoidance.

Birkby is 34 when he is sentenced and 40 upon release. He resolves never to return.

~ Epilogue ~

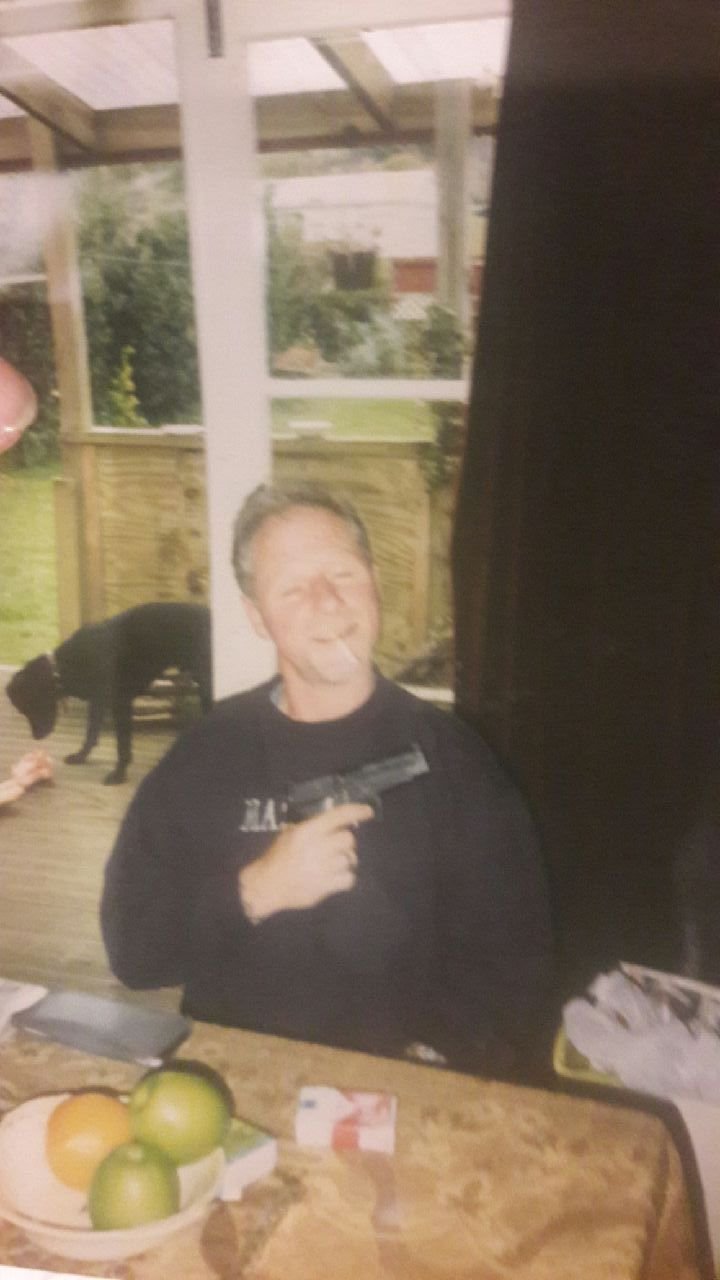

John Richard “Shotgun” Birkby, 2017.

Today, sitting across from me Birkby explains how he has found a better priority. One that does not risk imprisonment. One that does not hurt people, including himself. One that genuinely inflates him with a sense of purpose and self—his boys.

Yet, he says, he would not change a thing about how his life has played out. Prison reunited him with family, with his mum. Girls and drugs brought him good memories. But now he’s ready to make different kinds of memories.

He enjoys looking back to where he was—raging drug criminal—to where he is now—family man, with a $600,000 home he plans to bequeath his boys. Birkby tells me has given them something better than what either of his dads gave him.

“And isn’t that point?” he tells me.

“But don’t get me wrong,” he cautions, “I still like to say and do things to get reactions out of people. And if they don’t like it—they can fuck off.”

~ fin ~