An intangible place called home

Leili’s first solo show is as much an exercise in solidifying identity as it is uncovering the elusive rewards of being neither here nor there. Born to an Iranian mother and Australian father, their experience of belonging is spread between the lascivious club-lined streets of Sydney’s red-light district and their ancestral homeland of Iran. The stark dichotomy—of neon arabesques—goes beyond geography; it is embodied, absorbed corporeally, psychologically, existentially. Each painting, then, is a bricolage of ephemera, people, stories, and talismans, recalled from a life lived between place and between self. The collection is composed to offer a different vision—of diffuse realities converged—of what it is to have this cultural heritage.

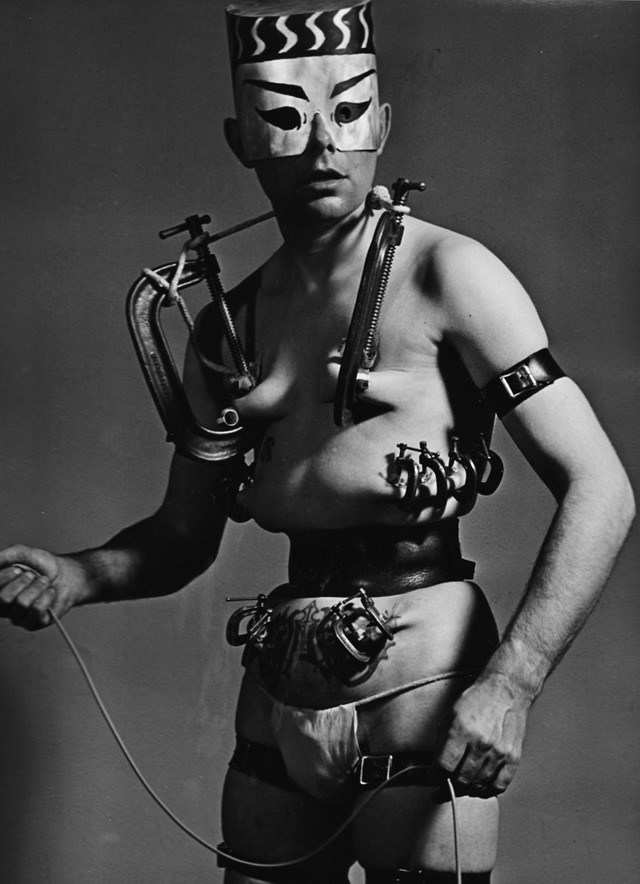

Leili. Photo: Frances Cannon

For Leili, thinking about what it means to belong, of finding a place where identity is reified and recognised by the people around them has always required engaging in abstractions. Being Persian-Australian and trans they radiate a level of ambiguity that eludes the homogenising function of binaries—too brown for Australia, too Western for Iran. Although their university degree in mathematics and philosophy has helped cultivate ideas on what it means to manipulate and play with objects in extended dimensions, the institutionalised pursuit of knowledge pushed them towards art.

Leili pays homage to informal pedagogical spaces in ‘College of Knowledge’. The family loungeroom was a space that always resonated with their father’s music; it provided the score to conversations and connections that came to define ‘belonging’. Today, these soft memories of home are recalled and informed by more recent experiences of place. As the late sociologist, Zygmunt Bauman, professed, disembeddedness is the central feature of contemporary living; however, few ‘beds’ for ‘re-embedding’ are solid or resilient enough to occupy. Such realities, of confronting rigid categories and porous spaces for identity building, would find Leili revisiting their academic musings on the philosophical implications of existing in dimensions higher than three.

“College of Knowledge”

For instance, if the prescribed models of femininity and masculinity reflect an oppressive way of being, it is not enough to merely collapse the binary into a third. Constructing self requires an untethering from both—to look beyond what’s available and scale into the abyss of something other than the sum of society’s parts. In this way mathematics provided Leili allegorical solace—it revealed a world of invisible certainties dancing beyond yet vibrating within. Since high school Leili’s thinking has been inspired by the theoretical underpinnings of Edwin Abbot’s Flatland as expressed in the book’s symbolic narrative: A dot meets a line but can only view the line as a point. The line explains what it is to be extended in its dimension. But a line meets a square and can only see its side—another line. But the square can explain what it is to exist in its dimension. Square meets cube, cube meets tesseract, and so on.

Taking time to listen when one explains what it is to exist in their dimension is a potent defiance against bias toward circumscribing difference and distilling complexities into palatable tropes—into dots. The more we enquire and remind ourselves that behind every dot is a line, the more comfortable we may become in our own divergence—of amorphousness—of taking up space once reserved for concrete categories. In the realm of material things, such abstractions tend to find light in art—coalesced and illuminated in the collection that surrounds you today.

The work both anchors and reflects the experience of being neither here nor there. The ubiquitous presence of waves illustrates how solidity is merely surface value, that ‘living in society’ is to float upon a swirling and ever-changing collection of agreed upon and shared understandings of meanings. Irrespective of how tenuously or tenaciously we feel our roots to be, fluidity is an experience shared by all. Leili’s work captures this jagged unison not in submission or certainty but by acknowledging the importance of recollection. They give form to these memories as though cultivating their personal Chahar Bagh.

Leili. Photo: Josh Milch

Gardens are sacred spaces. They demand a change of pace—a habitat to saunter and exchange stories among the vibrating stillness of nature. It’s where words and actions are made sense of against a different set of norms; where we might feel freer to self-create, more forgiving of transgression, and perhaps less inclined to moralise. The concept of Chahar Bagh, however, is highly structured and geometrical and has its origins in the Quran. This may seem counterintuitive but spending time in this atmosphere helps elevate chaotic ruminations into coherent and considered speech, a place to augur something better on the horizon. It holds space in a way we come to appreciate and nurture in friends, family, or community. This is the environment Leili invites you to occupy.

In Zoroastrianism, it is believed that a demon spirit called Nasu infects bodies of the deceased. Burial ceremonies were designed to avoid contamination of the earth. Bodies are placed in a Dakhma, an exposed circular stone tower, roughly translated as ‘Tower of Silence’. The bodies are cleansed of flesh by birds of prey and other natural elements. The skeletal remains are placed in a deep hole at the tower’s centre. Leili’s Dakhma is inspired by this process.

“Dakhma”

All rituals engage with death. They are structured to facilitate passing beyond a threshold to enter a new state of being. The transitional period, where one is positioned in a time and space disconnected from either origin or destination—neither here nor there—is known as a liminal stage. To be in a liminal stage is to watch the everyday world recede, a pseudo-death that demands immense sacrifice and suffering. But it is only from this vantage point that the possibility of a new realm emerges, one defined by its own set of shared values, myth, meaning, and emotion. It is only from this vantage point that a joy arises from the transcendent reality of sacred things.

Chahar Bagh is exhibiting at Backwoods Gallery from 01.07.22 - 17.07.22.

Opening night: Friday July 01, 6-8pm.

Backwoods Gallery, 25 Easey St Collingwood

Gallery Contact:

info@backwoods.gallery

www.backwoods.gallery

@backwoods.gallery