Radical Physiognomies: Meet two tattooists taking their face tattoos to the next level

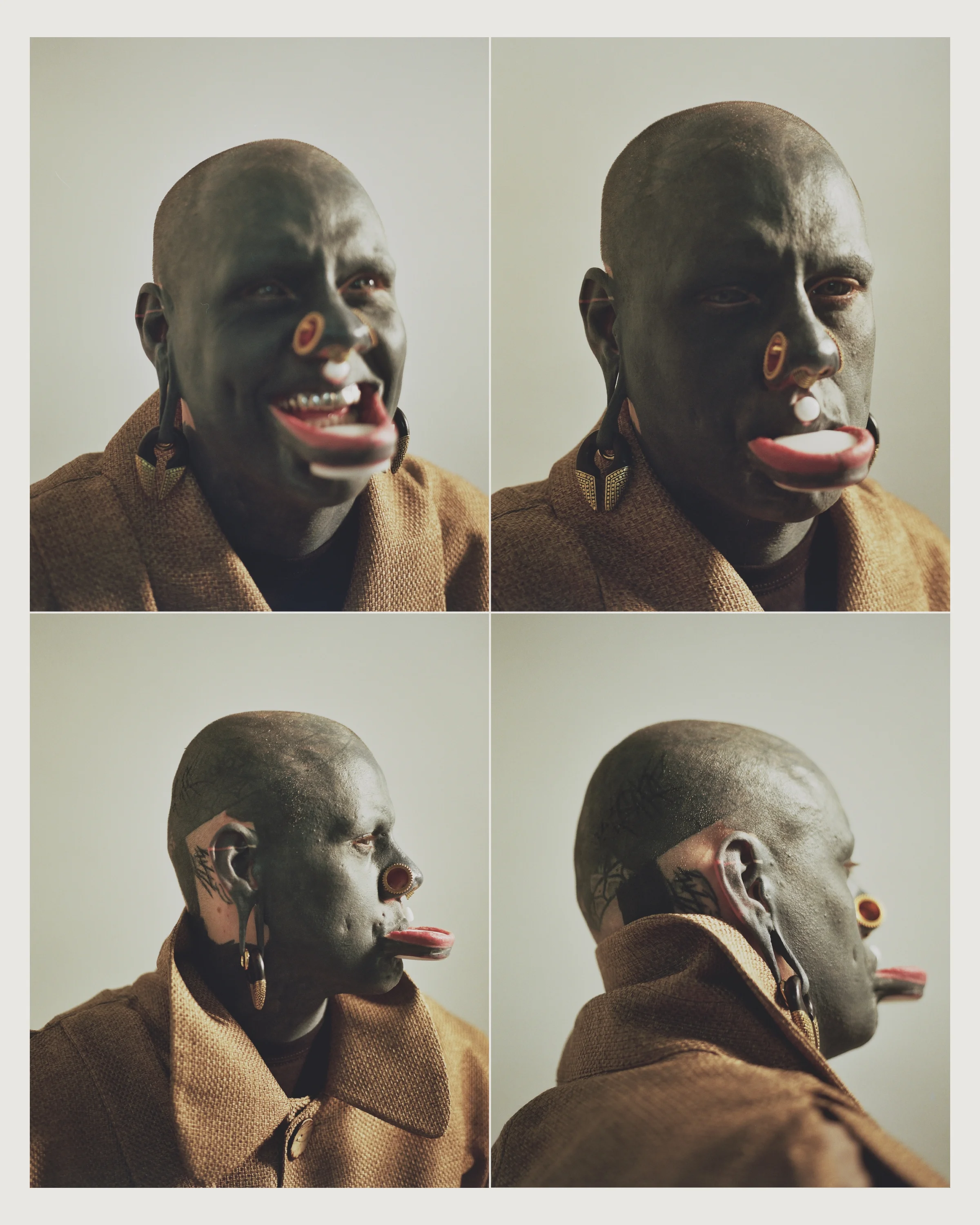

Eli (Photo by Richard Mensah).

As the most distinguishable part of body, the face is our portal to one’s inner character and temperament—we appraise its features, the tone and health of skin, and its shape to judge personality, trustworthiness, and beauty. For Eli, however, the face is just the face.

“It doesn’t play that much of an important role to me if I’m honest.”

From London, twenty-seven-year-old tattooist Eli is in the process of covering his body in blackwork—including his face, eyes, and every other crevice and cranny. Once finished, he plans to coat the base in abstract colours and marks; “I love abstract art,” he tells me, “Picasso, Jackson Pollock, and a lot of tribal mark making and tattooing.” His radical look caught the attention of fashion photography student Richard Mensah, whose photos of Eli, wearing garments designed by Ali Abdulrahim, capture an awkward and arresting friction—the vanity of high fashion upon the shoulders of a body that has resolutely fashioned itself into a piece of art.

Eli (Photo by Richard Mensah).

“The project with Eli stemmed from a university assignment which was titled ‘Radical Beauty’. My intake on that title was to separate both words: firstly, finding a subject that an audience or I find ‘radical’, then, by using well designed garments I would somewhat accommodate the word ‘beauty’ to merge both words.”

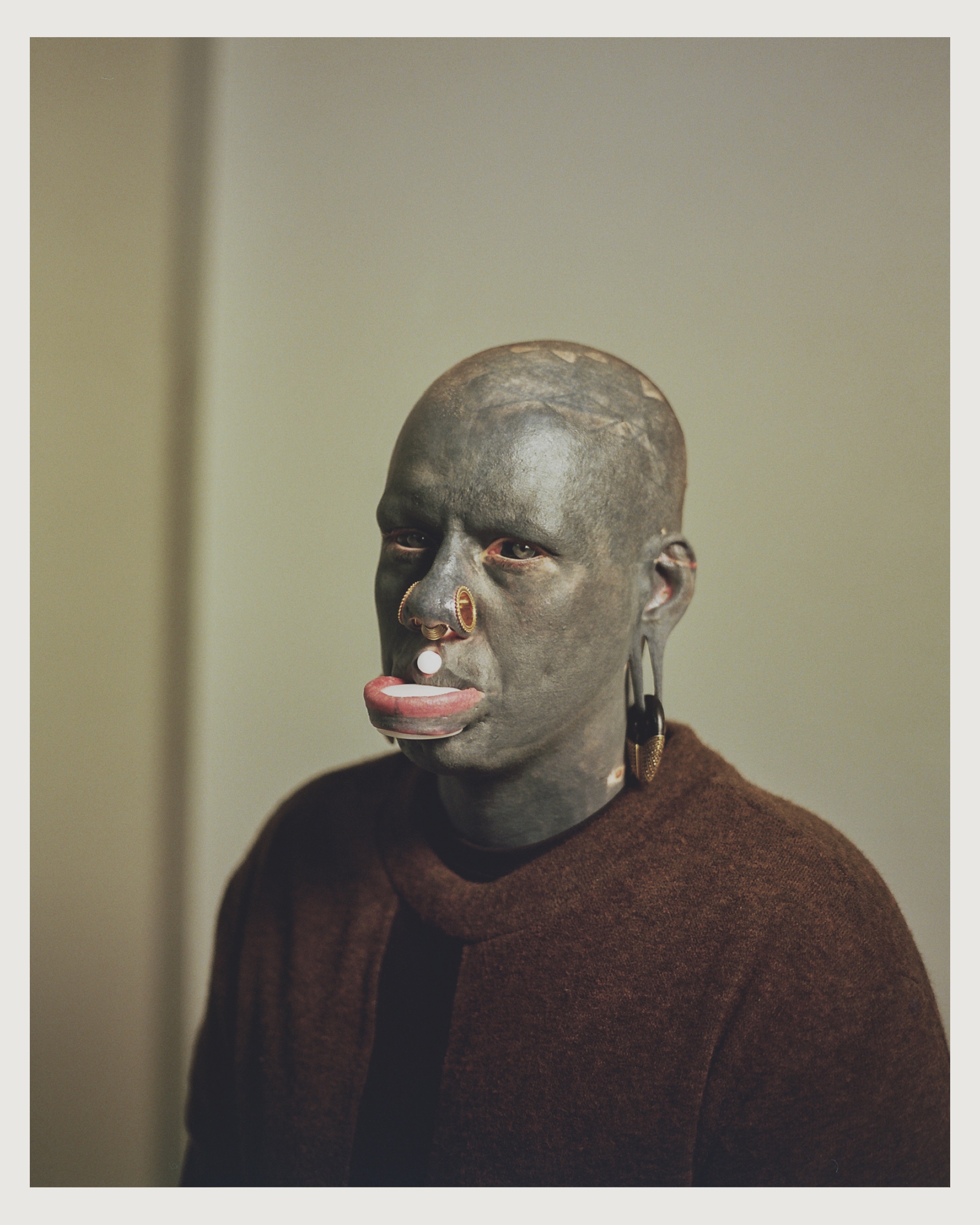

While his unique aesthetic could evoke references to some indigenous cultural practices in their use of lip discs and nose spacers, the imagery of Adam Curly’s physiognomy—another tattooist with a face masked in graphite tattoo, silver beard, and tattooed eyes—shifts the observer’s mental footing into a world of fashion fantasy and phantasmagoria.

Adam Curly

“I obviously don’t want my emotions to be read, as I am not human. I want to look like a hybrid of a werewolf and vampire.”

Originally from Poland where his appearance elicited physical violence and harassment—“people were throwing rocks and bottles at me, they spit on me in the streets, I was beaten many times,”—the alternative model and psychology graduate has now found a modicum of peace in London, “I still arouse extreme emotions, from worship to gag reflexes. You can’t pass me by indifferently, you either love or hate me.”

“This is my body,” he affirms, “I have the right to decide what I do with it. Some colour their hair, some colour their skin.”

Eli displays the same sentiment of bodily autonomy: “no one can tell me what to do with my own body.” For Eli, although tattooing the face was no different than his arms or legs, he did worry how long it could take getting used to the new visage—two weeks later, however, he was adapted and settled, but his journey nowhere near complete.

Eli (Photo by Richard Mensah).

“You’re always coming to parts that need topping up, or getting more layers to darken the skin. I’ll never be same again after this—tattooing solid black is a very spiritual thing, for me anyway. It rips apart from emotions. The pain in some parts is unbelievable and leaves you speechless for days sometimes. You can feel sick, faint, or you can feel happy and blissful. You never know what you’re gonna get. The more uncomfortable you are the more you grow. I learn more about myself the more I get in the chair. This is what I find interesting, is seeing how far I can go into mind.”

For some, their respective physiognomies could represent a capacity for intense experience and devotion, while for others—as the pertinent cue for those wishing to draw assumptions about his character—they may struggle to make sense of it.

“I don’t ever try to make people understand because the people who understand will be attracted to it and the people who don’t wont. People react the way people react—some pathetic and over the top, and some people really interested and have kind things to say. I’m not here to make friends or to make enemies, I’m here to make art and leave a mark. People can say what they want to say but unless they know me in real-life they will never know the truth. This keeps me humbled.”

Eli (Photo by Richard Mensah).

Eli’s matter-of-fact perspective is borne out of the keen focus and discipline needed to become heavily, and radically, tattooed. It’s a frame of mind shared by Adam, who says the people he chooses to surround himself with are supportive regardless of his appearance.

After a bout of colon cancer, the thirty-two-year-old developed vitiligo, resulting in the loss of skin colour. With the cancer also came depression and numerous nutritional disorders. It was here that Adam gained from becoming heavily tattooed what he lacked in life, a force to believe in his abilities and strength.

“Tattoo for me is not a style or trend, as everything passes. Tattoo is a proof of courage and presence. I stopped listening to the voices of blame—you only live once, so you should live it as best you can. Every day I smile a lot and show that you can live different, that you can live better.”

Adam Curly

As with Eli, who admittedly tries not to complicate his thought process by keeping everything step by step and focused on his bodily autonomy, the process has humbled him. Somewhat paradoxically, by drastically modifying and drawing attention to the skin, both Eli and Adam have pulled into focus that which truly distinguishes the character of an individual, “different skin colour should not dictate people’s reaction,” Adam says, “it is important to be a good person, to love and be loved.”

“There is too much hate and madness in people. Beauty is not what we wear, beauty is the attitude we represent.”