Festival of Dying: Is Your 'Death Literacy' Lacking?

“Missing.”

“Transcendence.”

“Pain.”

“Stardust.”

As if on queue ethereal static filled the boat shed, a microphone was adjusted, the crowd resumed sharing their single word associations for the weekend ahead.

“Rebirth.”

“Mysteries.”

“Stillness...”

I had travelled to Sydney from Melbourne to attend the inaugural Death and Dying Festival–not to be confused with Brisbane’s Deathfest–both of which are coincidently transpiring over the weekend. Over two days, speakers will impart their esoteric knowledge and practical skills about death and dying through lectures and performances on topics such as posthumous fashion, musical thanatology, and thresholds and lust; “we wish to make more appealing what many of us are very frightened to think and learn about,” reads the festival blurb.

It’s Friday evening and the festival’s director, Dr. Peter Banki, begins the opening ceremony by sharing a quip: “a friend of mine said, ‘I can’t imagine what a festival of death and dying would look like,’ to which I responded, ‘me neither’.”

I think it fair to say that, below the horizon of silver feminine coiffures sit brains in harmonious agreement. And it’s true, the crowd is mostly populated with female quinquagenarians and older, yet several younger faces are visible despite the boat shed’s mood lighting. I genuinely wondered whether it was suffering, inquisitiveness, or a terminal diagnosis that drew these attendees. To be completely candid I did think to myself, “how many of these people are dying, like, faster than they’re living?”

Nobody close to me has died; my death literacy is below rudimentary–potentially, I have a lot to gain from the weekend. I’m here to, as curatorial advisor, Victoria Spence, proclaims during her opening bit, “build muscles in relation to mortality.”

Several applauses later and the opening ceremony begins to close in the same haunting fashion it opened, with Adnan Baraké shredding on the Oud. And just when I think nothing could evoke more gut wrenching melancholy than a Syrian playing the Oud at a Death and Dying Festival, a fucking fog horn ominously bellows from some distant Ocean Liner beyond Rushcutter’s Bay, successfully executing a sombre aura of doom.

It’s 2:30am and, as I sit and type in my Elizabeth Bay Airbnb–the opening ceremony dirge still resonating in my head–I find my only source of solace in sleepily recalling Nietzsche’s (naturally) pithy rumination Peter Banki recited by way of introduction to Adnan: “without music, life would be a mistake.”

Day 1:

'Finish this sentence: When I think about the state of the world I feel…'

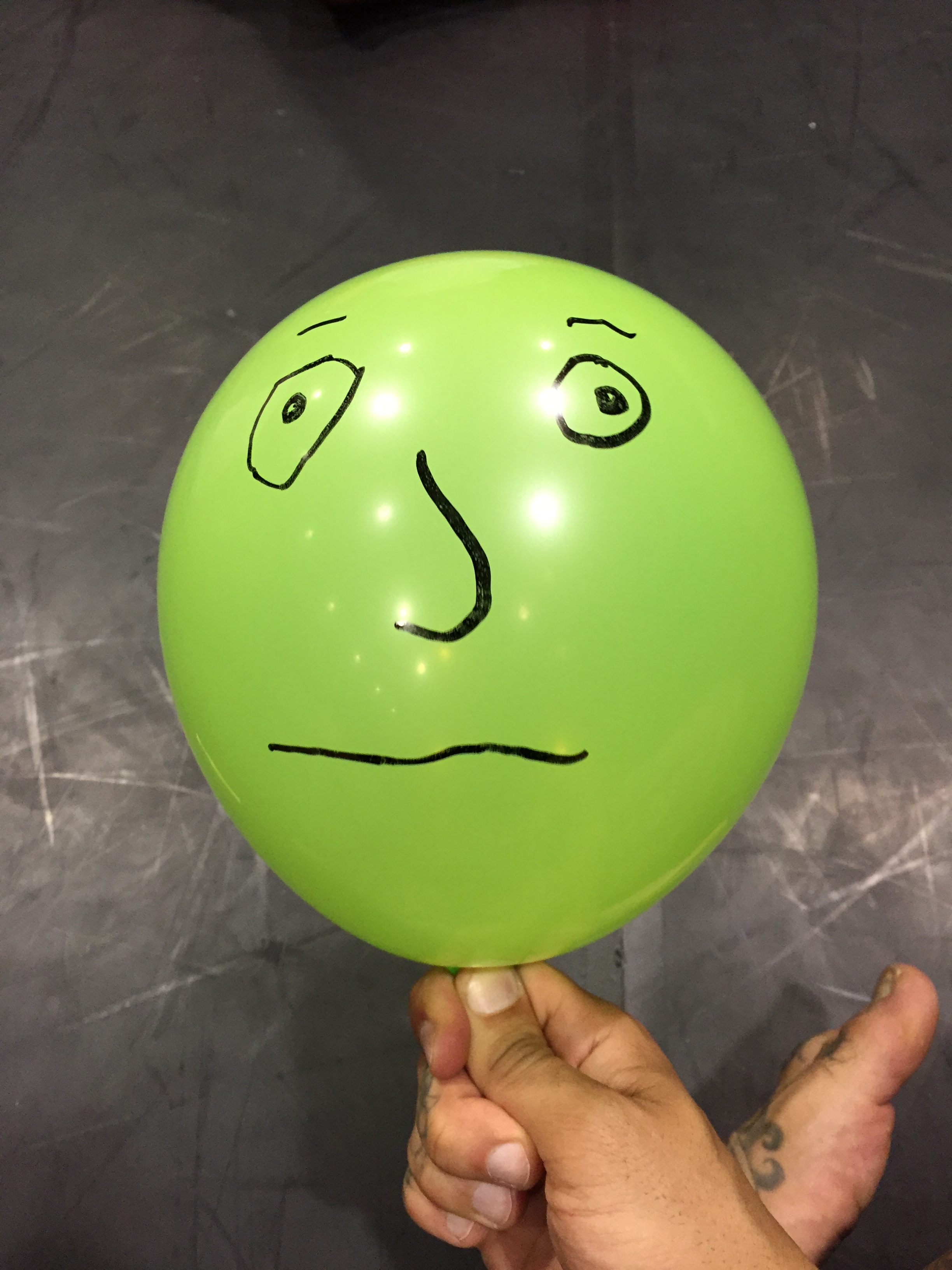

I’m confident green balloon visage neatly captures the emotional trepidation a lot of us are feeling in this particular point of history. I have arrived 15 minutes late (9:45am) to my first workshop, The Personal and the Environmental, and was told to draw a face on an inflated balloon. Scanning the twenty or so participants I note plenty of new faces, both young and old.

Our tutor, Dr. Sebastian Job, explains how he believes the grief and anxiety we harbour about different deaths, namely, our own and the ecosystem’s, may contribute to a collective paralysis, and disables us from acting. He posits that if we were to ‘face the worst’ ahead of time, in the form of a symbolic death, it could provide an opportunity to process the anxiety and clarify personal causes of inertia, which he calls our ‘dragon’.

So we’re told to think about the state of the world and write down how that makes us feel. I scribe adjectives like hopeless, embarrassed, angry and powerless. We’re asked to imagine ourselves in conversation with Earth, “what is the ecosystem saying to you, why aren’t you answering the call, what’s stopping you?”. My Earth says “help, you fuckwit! I’m dying!” To which I reply, “Sorry! I’m not in charge, I feel so helpless! I don’t know what I can do for you, big man. I recycle?”

The ritual entails inflating a balloon, while blindfolded, until it bursts. This is more confronting than it sounds. It sounds intense and goes against my better judgement, so while everyone around me is symbolically passing with violent explosions I’m wondering if I could go out like a tragic-comedy and let the balloon sail through the sky passing wind. But I blow until it pops and I collapse to the ground, physically startled. People are dying around me, I can hear sobbing but I’m not sure if it’s PTSD being triggered or a transcendental experience. We regroup and share our dragons, workshopping various ways to slay them.

“Death is not a design flaw, it's how we mature and engage with life on life's terms, how we are formed and shaped anew.”

Next up, Developing Your Mortality Muscle. The class is large and I nestle into one of the airbeds scattered throughout the hall. Victoria Spence is a civil celebrant, consultant, andformer thespian. She begins by gesticulating her objectives: creating death literacy in the social realm of death and dying.

When referring to death, Victoria speaks of working out–in the muscle building sense–one’s sematic intelligence. That means being aware of, and understanding, one’s physiological response to loss; death may cause us to fight, flight, freeze or submit, however, shock will always occur to a varying degree. We react by abruptly drawing in breath and, Victoria says, we metaphorically keep our breath held during death rites. Being prepared–building muscles in relation to mortality–equips us with the tools to breathe and be present throughout.

Becoming an expectant parent cajoles one into months of autodidactic preparation, workshops, shopping, and major life adjustments.

Becoming bereaved is often unexpected and sudden–there are no preparatory months, we’re thrust into a dialogue with foreign somatic and emotional activity, and Victoria is teaching me the physiological dialect of death and dying. Her next class, Being With Your Dying and Your Dead, takes this discourse further.

“When somebody dies you put the kettle on. That's how you be with your dead.”

Although Victoria is referring specifically to a home death scenario, her comment is also metaphorical. We need to learn to be present with our dead. Having physical proximity with the deceased, being privy to their new smells and witnessing physical changes, lays biological precursors to grieving.

Victoria opines the benefits of allowing yourself an intimacy with death–the tactile is visceral–to have your person home, to bathe and clothe them. Although many death rites have become commoditized playing an active role in them is still possible, all we need to do is ask.

Now we’re given the chance to get up close and personal with the accoutrements of death, so I slink into a satin lined coffin, not before somebody notes my ironic choice of t-shirt, to which I have been completely oblivious, and as the lid is repositioned I imagine the sound of dirt raining down on me.

Me

I’m resurrected in time for the final workshop. I feel exhausted. The engagement and emotional maturity of everyone is palpable. I sense that I’m out of my depth, but I don’t feel uncomfortable. On the contrary, I’m intrigued and excited for the next class: From Music into Silence.

“The choice of song is almost irrelevant because what you want is your next breath.”

Peter Roberts is a music thanatologist. He plays music for people who are at the end of their life. Using music in a prescriptive manner can assist people to let go. And several have during his service.

Tempo can temper breathing, the tone and timbre of Peter’s harp can quell fear, his use of vowel sounds, not words, can offer uncomplicated companionship, and provide the dying an intimate narrative by which they can abandon their pain riddled body to follow with their mind.

While Peter plays the harp for us an image of a child dressed in tubes staring vacantly past Peter’s harp is projected onto the wall My empathy valve is fully dilated. This is followed by an image of a woman nuzzled into her dying husband’s body while Peter sits bedside, playing his harp...

Day 3:

An image from the performance night. Photograph: David Brazil Photography

I didn’t attend last night’s performance and I missed this morning’s lecture. It was a long, hot, and emotionally draining day yesterday so I caught up on some much needed Zs. Upon my arrival I purchase a vegan slice from the in-house caterers and skulk to observe friendships forming, information exchanged, and future plans made. The festival has facilitated the birth of a community.

Another image from the performance night. Photograph: David Brazil Photography

“We all know what consciousness is until we try to explain it.”

My first session is Dreams and Visions at End of Life. After Dr. Michael Barbato, a palliative care physician, acknowledges the traditional owners and custodians he dives into a story Andrea Mason shared at a conference he attended several years ago, the gist of which goes like this:

An Aboriginal man is slowly walking down a desert road. A ‘hoon’ driving a souped-up car down the same road stops to give him a lift. He accepts. They drive and the Aboriginal man is visibly distressed, clutching at the seat with white knuckles. The driver asks what’s wrong. The man asks to stop. The driver asks why. The man says ‘you’re driving so fast that my body is here yet my spirit is still back where you picked me up, and I need to make time for it to catch up.’

Dr. Barbato explains how this vignette is a metaphor for where we are in palliative care–we have the best care for the body but the spirit is all too often left behind.

Dr. Barbato believes we overlook the mystic elements of death and dying simply because they appear fringy. Throughout his talk he shares several enthralling accounts of peculiar death bed events where patients (he stresses his dislike of this word but acknowledges its efficacy) either appear perturbed apropos of nothing, engaged in conversation with apparitions, or yabber jabberwocky. He quotes a study he conducted with families of deceased, asking if they noted anything awry around the time of their loved one’s demise. He found that up to fifty percent of respondents believed their dying loved one was experiencing unusual visions.

Needless to say, the Palliative Medical Journal refused to publish it because it was too fringe.

Dr. Barbato appears to be a kind and selfless human being, and although his talk is entertaining and peppered with emotive stories, I’m finding that it lacks the scientific substance I require to get into the moment.

And when he reveals that his mother was a psychic, I tap out.

“Proximity to death can make us feel alive”

Thresholds and Lust is an intersection of both of Peter Banki’s festivals, Death and Dying and the Festival of Really Good Sex.

When we speak of death, Dr. Peter Banki says, we often use words like pain, fear, and submission. His workshop is designed to playfully evoke these emotions from willing participants.

Participants pair up, one embodying the role of master while the other submits. My partner places a bondage hood on my head, suffocating my senses. She engages with my body by running her hands over my arms and head and manipulates my legs to an extended position. I can’t help but wonder what everyone else around me is doing–are they watching?; the heat is baking my gimp head like a potato jacket and my body is uncomfortably contorted on the pungent floorboards. I tap out.

I realise I’m not yet ready to yield to the vagaries of dying, whether real or imagined, but I do notice I have begun cultivating a relationship with death and I’m thankful for that. And although the festival could have benefited from some cross-cultural explorations in the end it’s a festival for everyone. I mean, you’re all dying.