The untold story behind the "father of contemporary body modification" is one of racial exploitation

“I grew up tempting my primitive lust by reading good old National Geographic.” —Fakir Musafar (in Modern Primitives)

Body modification is more visible and ubiquitous than ever before. Branding, cutting, scarification, subcutaneous implants, earlobe, nostril, lip and labret stretching, hook suspension, corseting, tongue splitting, navel removal, pixie ears, whiskers, genital and digital nullification—all these processes intrude on and manipulate the body, redefining cultural boundaries of beauty, identity, and what it is to be human. Many have traced the Western inception of this phenomenon to the iconoclastic spirit of one individual—Fakir Musafar.

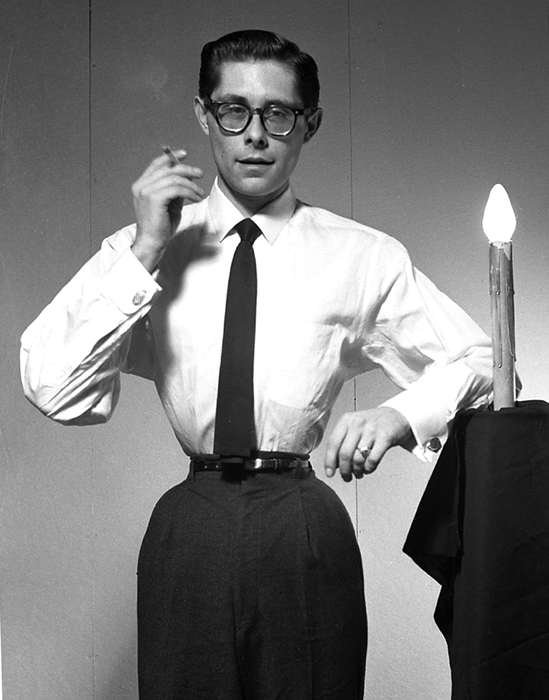

Born Roland Loomis, the ex-advertising executive turned self-proclaimed shaman took his name from a nineteenth century Sufi who spent eighteen years with daggers piercing his body. In the same vein, Loomis’ life was spent manipulating flesh in search of the spiritual, transcendent and transformative. A recent article about extreme forms of beauty credited him as revolutionising and radicalising the concept by introducing modern society to extreme body modifications. The article indulged some commonly afforded accomplishments—“integral to the birth of modern piercing culture”; “father of contemporary body modification”; “pioneer of contemporary body hook suspension”. The piece went so far as to declare him the creator of some of “history’s most extreme body modifications”.

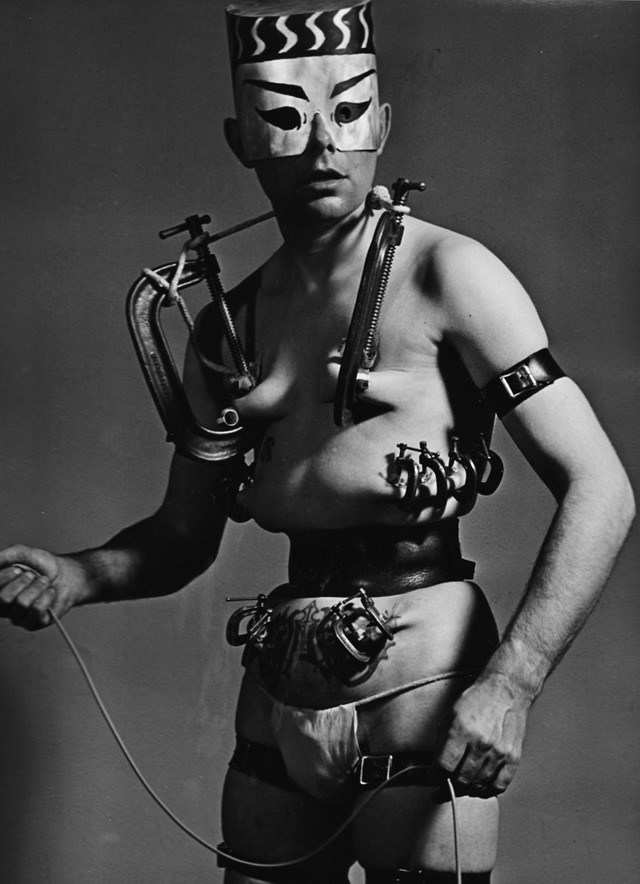

Fakir Musafar

Indeed, ostensibly, he was those things. During the 1940s, at age 14, Musafar was piercing his foreskin, a time where he harboured a legitimate fear of being thrown into an insane asylum for the act. At 17 he was tattooing himself with sewing needles and India ink. At 18 he wrapped a belt around his waist and pulled tight, wearing it frequently for thirty years permanently fixing his waistline to 24 inches. At 33 he pierced his chest with wires and fashioned them into hooks that took the full weight of his suspended body. During the 70s and 80s, with the patronage of Doug Malloy, Fakir Musafar and Jim Ward took the practice of piercing from the diffuse enclaves of punks and gays into the skins of middle-class Californian urbanities.

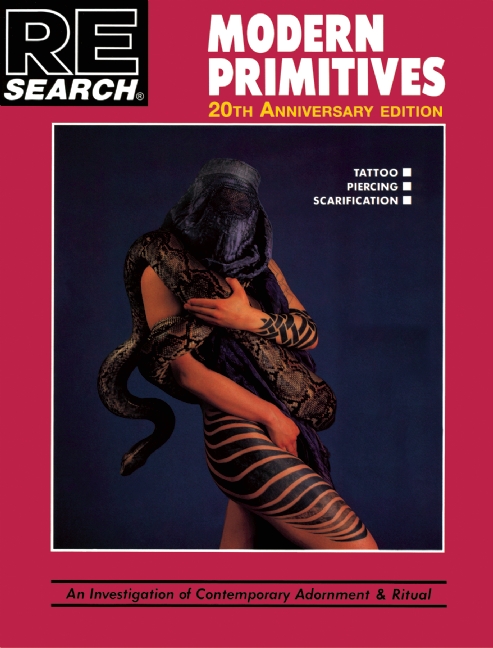

But his most significant contribution to pioneering extreme body constrictions, encumberments, modifications and piercing was made in the 1989 publication, The Modern Primitives: An Investigation of Contemporary Adornment and ritual. The 212 paged book contains 22 interviews and 2 essays with predominantly white practitioners and enthusiasts of tattoo and body modification. The authors, V.Vale and Andrea Juno, expected to sell only a few thousand copies. Ten years later over 60,000 copies in 6 reprints had been sold. In 2008, the number was at half a million and 13 reprints. The book stands as the canonical text that brought subterranean and fringe body practices to a vastly greater audience[1].

“That one more than anything else had my message in it,” Musafar declared of Modern Primitives, “and it has inspired more people than I can dream of.”

It was here, spread across 30 pages, that he outlined the philosophy of his oeuvre. Musafar had coined the moniker “Modern Primitive” to define any “non-tribal person who responds to primal urges and does something with the body” within a ritualistic context, preferably one emulating tribal practice. His fascination with indigenous modification and ritualistic practices was transcribed alongside images of him performing them. The dialogue was populated with countless references to a multifarious and random selection of non-western body modification rituals, or what Anthropologist, Daniel Rosenblatt, would later observe as “the whole history of Western speculation about other cultures… tossed into a blender with more than a little New Age mysticism and some contemporary sexual radicalism thrown in besides.”

Musafar spoke of how Compton’s Picture Encyclopedias, a multi volume set of encyclopedias compiled of thousands of illustrations and articles, had inspired a desire for a small waist line: “I saw another picture in an encyclopedia of an Ibitoe,” he would explain, “a wasp-waisted boy of New Guinea. It said above all things, these people admired a well-spiked nose and a small waist… I would become the Ibitoe.” He conveyed his fascination with the tattoo practices of “Eskimo”, New Guineans, and North Africans, and expressed avid adoration of the Native American “Sun Dance” ceremonies, Mandan O-kee-pa ceremonies, Sadhu Indian penis stretching, indigenous Australian penis manipulation, and Indian Kavandi-bearing.

Although Musafar had read the whole encyclopedia in his early teens, it was one publication in particular he claims ignited his “primitive lust”.

“Taken as a whole,” he said in Modern Primitives, “the old National Geographics constitute quite a compendium and survey of primitive practices.”

In fact, the magazine not only inspired but informed most of his early rituals and modifications, acting like a one-dimensional visual guide.

“I knew nothing about piercing but I had to have this hole in my body,” he would admit in Modern Primitives, “I had seen a picture in an old National Geographic of an old South Seas Island man who had just had a child; he was a father. So as a father he was entitled to have a hole bored in his nostril. In the picture, the caption was all I had to go by.”

He also credited National Geographic’s photographic journalism as the inspiration for his first tattoos.

“I guess I was influenced by all of the reading and all of the other cultures because that's what it's all about in Borneo or Marquesas Islands. It's not done solely for decoration, it's part of an initiation, a rite of passage. It's part of transformation.”

Musafar had seen in “primitive” tattoo and body modification a function hitherto not found in his contemporary Western context; non-tribal tattoos and body modifications, he argued, lacked ritual, thus, meaning gets lost along with its rich transformative and sacred power and rewards. It was his desire—which became his life’s work—to import that “primitive” aspect to a society he saw as fractured and profane, too civil and outward looking to realise the latent magic within. For many readers of Modern Primitives, it was their first time seeing a human hanging from flesh hooks or connecting body modification with spirituality. Although the book’s author V.Vale admitted the publication was an exercise in amateur anthropology, the absence of critical analysis did not preclude it from becoming the most widely influential volume on body modification practices to date.

Yet, the source and language of Musafar’s beliefs and practices were problematic, to say the least. A recent National Geographic editorial boldly admitted to failing in its role to present accurate and authentic depictions of anybody that was not white—“For decades, our coverage was racist,” read the blunt 2018 title. Elucidating on the magazine’s appearance at the height of colonialism, Susan Goldberg acknowledged how non-white subjects were presented through the colonial gaze, as exotic “natives”, unclothed and “happy hunters”, “noble savages”. In other words, the magazine’s imagery merely functioned to further subjugate the racialized other—silenced and exposed to the imperialist’s gaze. Not surprisingly, these same racist tropes permeate Musafar’s work, albeit in a partly reversed form, presenting “primitive” practices as the antidote to centuries of colonisation, modernisation, and Christian proselytization—the purpose of reviving “primitive” activities, he would claim, was the desire for a more “ideal society”.

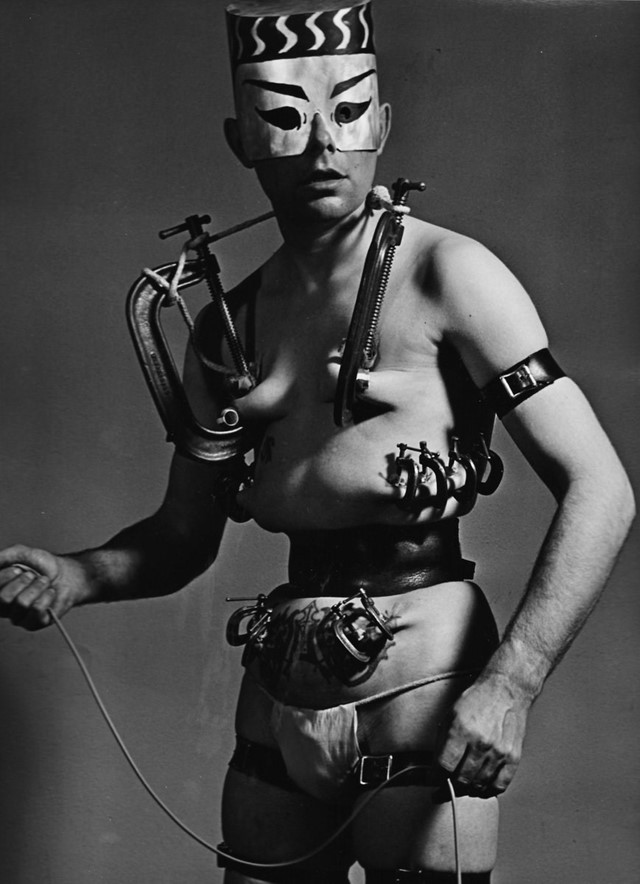

Fakir Musafar “performing” a Native American Sun Dance Ceremony

Prescribing primitiveness as panacea for Western woes is not a new diagnosis. In fact, the intellectual scaffolding upon which Musafar’s ideas gained credence were the same that justified European conquest to begin with—the essentialist binary of ‘civil self’ and ‘savage other’. It is when we reacquaint ourselves with this history of demonising and erasing indigenous cultural and spiritual practices that the sacred shroud with which Musafar dressed his modifications and mimicry[2] render them culturally insensitive acts of ignorance and theft. By failing to engage with non-European people with respect to their heterogeneity, complexities, varied histories, and agency, he presented them like salvaged exotic plunder, their cultural practices plucked and sampled to “remedy” white malaise and ennui. Musafar’s contribution to contemporary body modification culture cannot be overstated, however, it is important to understand on who’s backs this subculture was built.

§

“We knew that we were not Indians and we could never have access to doing this as an Indian. So, we decided, being non-blooded Indians, and not knowing all that much about the myth and heritage behind it, that we would go out into the wild, into Wyoming, and do a Native American Sun Dance as best we could, our way.” —Fakir Musafar (in Modern Primitives)

During the 60s and 70s categories of class, gender, race and religion started to become ambivalent and unstable markers for identity. The rise of previously subjugated voices—such as women, blacks, and other marginalised groups—began to challenge traditional hegemonic structures of meaning, knowledge, and value. Erik Erikson, the German-American psychologist famous for coining the term identity crisis, described it as the era of “identity crisis”, where the formerly repressed energies of social movements and activists burst into the mainstream, facilitating a shift from social conformity to cultural revolution. They were an indictment of modernity; the limits of reason, democracy, religion, and unfettered industrialism manifested itself in imminent nuclear obliteration, war, fascism, patriarchy, the genocide of indigenous cultures and peoples, and global environmental degradation.

For more people the widening dimensions of choice—unless obstinately circumscribed by race, gender, class, ability and ethnicity—rendered identity as something to be manufactured rather than emerging from one’s social position. The historian, Eric Hobsbawm, saw individuals scrambling for groups to which they could belong into a “world in which all else is moving and shifting, in which nothing else it certain”. The general mood of the time was one of ontological insecurity and anxiety.

Although Western thought had a tradition of demonizing any discourse surrounding the body not based in science or, paradoxically, Christianity, the conditions of late modernity were such that, for many, the body became a reliable foundation for individualised identity building, something social theorist, Chris Shilling, called “Body Projects”, or what Musafar termed “Body Play”.

Fakir Musafar emulating an Indian O-Kee-Pa-Ceremony

“Today, a whole part of life seems to be missing for people in modern cultures,” Musafar declared in Modern Primitives, “whole groups of people, socially, are alienated. They cannot get closer or in touch with anything, including themselves… well, there have got to be some remedies and they’re going to come from some very strange places… It all comes down to: it’s your body, play with it. For a long time western culture has dictated: don’t fuck with the body; it’s the temple of God. But finally people are starting to see things in a different way…People need physical ritual, tribalism – they’ve got to have it, one way or another.”

It was the 70s and tattoo began experiencing a Renaissance. Pioneering tattooist, Cliff Raven, saw the revival as reflecting the end of America as a melting pot: “Tattoo is one way of reassuring, or reinforcing, the ego under pressure. It provides an expanded, alternative, volitional identity: one can come to terms with the psychic constraints of the slot(s) one occupies in society.” Political, social and technological shifts were accelerating and shaping culture. Key European tattoo artists were travelling to Asia and the Pacific bringing home new techniques and styles. Flash art was failing to meet the complexities of self-realization; frontline tattooists such as Lyle Tuttle, Spider Webb, Cliff Raven, and Ed hardy were advancing the practice into large-scale, custom, full-body designs quite evolved from the limits of pre-congealed, formulaic and limited iconography of Western motifs. To accomplish large-scale full-body work like those common in Japan and Polynesia offered revolutionary potential for the bodies and identities of Western individuals, “to be able to transform somebody that much seemed truly spectacular,” Ed Hardy recalled, “that didn’t exist in our society.”

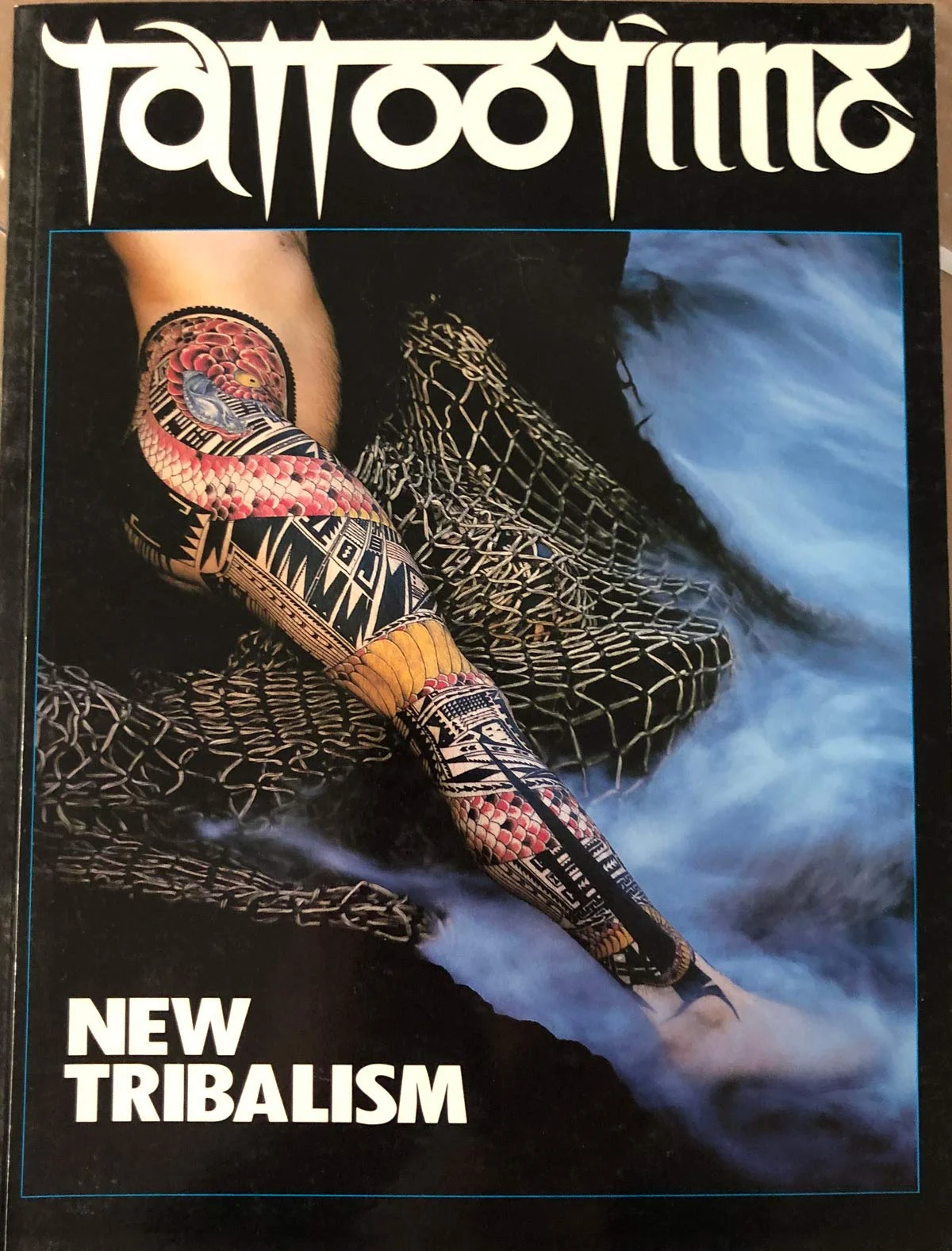

Ed Hardy and Le Zulueta’s Tattootime, New Tribalism issue.

In 1983 Ed Hardy and Leo Zulueta decided to create what became one of the earliest records of the bourgeoning modern tattoo industry—Tattootime. The first issue included powerful black graphic work featuring designs predicated upon Polynesian and Marquesas motifs, or, as Hardy put it, from “so-called primitive societies”. They jokingly entitled the volume “New Tribalism”, amusing themselves with what Hardy would later recall as the “outlandish notion” that the style would catch on. After publication it became apparent that, notwithstanding the diversity of growth in the industry, the anthropologically inspired blackwork was becoming ubiquitous. Hardy and Zulueta had given birth to a style movement.

Musafar saw this as evidence of a “primal urge” for tribalism and ritual; Hardy, however, resented the connection.

“It’s intriguing to see it [primitivist discourse] used by people as essentially the new kitsch. They’re not very original designs, but they pick up on this thing how it’s meaningful for them, how it’s a journey or a rite of passage and all that stuff, and it’s kind of incredible that that’s going on…I get so sick of hearing all that stuff, and of course I know that I started a lot of it because I started focusing on that in the first Tattootime, just kind of to make people aware of it, but it’s just so corny now.”

Until that point, tattooing in the West had never been articulated as a sacred or existentially transformative experience. Although the history of European tattoo is disparate and disconnected, its meaning and function was never universally codified or understood in the same way indigenous communities made sense of and employed the craft. It was a structure of meaning Musafar believed was detrimentally absent from contemporary Western tattoo and body modification. Yet, the intellectual kernel of his foundational claim—that modern culture is defined and bereft by the absence of tribal ritual—had its roots in another, more defining Renaissance.

§

“That whole Judeo-Christian belief system imposes an absolutely negative connotation on tattooing. It’s a basic human tendency to want to decorate one’s body; it’s something people have always done. Yet this society doesn’t provide any place for it, and the cultures that did have indigenous tattooing were pretty successfully wiped out by the Christian missionary intrusion covering the world with white Western culture.” —Ed Hardy (in Modern Primitives)

The seventeenth century rebirth of ancient Greek and Roman knowledge saw French Renaissance thinker Charles De Montesquieu refine ideas about human nature and society by proposing it evolved along three linear stages: savagery, barbarism, and civilisation. His conceptualisation of human history became known as social evolutionism, which, alongside many other new ideas spurred by the impact of new empirical and rational sciences and philosophical and political revolutions, coalesced to undermine the Church’s dominant authority and gave birth to what many regard as the beginnings of modernity.

One of the most influential voices of this Age was Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the French essayist championing individual reason and the human capacity for enlightened social action. His diatribes lambasted the State’s unjust structures and subjugation of Man. Rousseau became obsessed with trying to establish an image of how life might be lived outside their rule. Contrary to the Hobbesian notion of a brutal and short existence in lieu of State protection, Rousseau dignified the state of nature. He believed in the existence of a natural, egalitarian condition of man free from government abuse and authoritarianism, one that would not succumb to savagery. Although the term ‘noble savage’ has its etymology elsewhere, English translations adopted it to describe this mythic personification of utopian citizenry.

Joshua Reynolds Portrait of Omai

In 1768 the Royal Society commissioned James Cook’s first voyage to the south Pacific Ocean. In the spirit of the new Age of Enlightenment, it was scientific in nature; the body of knowledge to be discovered would serve as a blueprint to build a solid, useful, and modern philosophy upon. The engravings of Cook’s Polynesian visit became the first to illuminate an image concurrent with a natural free man; there stood the noble savage, poised amongst a vast landscape—like that of Eden before the Fall—in a state of untamed nature, just as Rousseau had conceived it. This poignant manifestation of the noble savage was embellished by Cook’s engravers and European publishers who idealised and ennobled the inhabitants, drawing parallels of their customs with the ancient Greeks to elicit the question of whether perhaps the natives, living “exempted from care, labour and solicitude,” may not be better off than European man.

As the romanticised picture of Polynesians grew, an interest in their more ‘savage’ practices, such as infanticide, cannibalism, and tattoo, roused the London Missionary Society’s (LMS) proselytizing spirits. Pacific art expert, Anne D’Alleva, noted the LMS chose the Polynesian Islands as their first pacific mission precisely because “the island had been so widely—and, to their minds, wrongly—celebrated as an ideal land where people lived, like the ancient Greeks, in innocent and natural splendour.” Throughout most of Polynesia, particularly in the East, Christianity all but effaced the ancient, sacred institution of tatau. The missionary perspective became hinged on the question of tatau’s relationship to religion—the stronger its association with the sacred, the more likely it was to be eradicated and outlawed. Traditional systems of meaning, political and social structures, religion and sacredness were systematically replaced, to varying degrees and character, with European customs and God.[3]

Christianity’s attempt to gather the world’s theological curiosity expanded alongside European imperialism’s quest for global dominion and ‘modernisation’. The Polynesian example highlights how European colonial conquest would employ, to varying degrees, scientific and Christian discourse to separate indigenous bodies from nature, estrange them from culture, and subsume their sacred and spiritual worlds into the exclusive domain of the Church, rendering anything outside profane. The myth of the noble savage remained a fixture within European consciousness, commonly evoked throughout the colonising project; indigenous populations were only ever understood as the ancient, primitive ancestor to “modern man”. As Associate Professor of history, Helen Gardner, eloquently put it, “metaphors of time forged the social relationships of colonialism.”

Although missionaries and colonists were denying indigenous cultures access to their body modification rituals, sailors were often inspired by their encounters to decorate their own skins with motifs and styles peculiar to their own culture and beliefs. There are many records of these early cultural exchanges—first peoples tattooing sailors and, to a lesser extent, vice versa. But, when back on Western shores, sailors and other tattooed bodies were subject to a representation of the body that was confined to the modern sphere of medicine and social biopolitics. For instance, around the 1870s Cesare Lombroso, an Italian physician often referred to as the father of modern criminology, conducted several now infamous studies on prisoners concluding that criminals were throwbacks to a more primitive type of man in whom morality, physicality, and temperament were underdeveloped. These men, he believed, could be diagnosed merely by observing physical characteristics such as large ears, long arms, a sloping forehead, prognathic jaw, and tattoo. He attributed the desire to become tattooed or modify the body as a vestige of premodern simplicity and atavistic tradition. These ideas influenced formal academic studies of tattoo up until the 20th century.

It was not until the latter decades of the 20th century that the body emerged as a valid place to construct a new way of thinking about the world and identity. As trust in Christian dogmatism and Western rationalism declined, a spiritual instinct remained active. The church, having lost control of the body, had left it open for re-enchantment. The “turn to the self” became the mantra of New Age Western mystics during the 80s and 90s as they developed innovative realms for individual fulfilment and inner spiritual harvesting. In designing a blueprint for an alternative self, however, Fakir Musafar relied on sustaining the racialized discourse intrinsic to evolutionism.

By employing primitivism to reject the rational reductionism of human experience, Musafar premised his beliefs on what Associate Professor of Political Science, Virginia Eubanks, viewed as the illogical attempt to salvage an authentic primitive and “(re)construct a link between ‘our’ fragmented culture and a ‘natural’, ‘tribal’, ‘primitive’ culture.” The romantic stereotype of the noble savage served as justification for cultural theft and authentication for what was essentially a theosophical tradition embracing a romantic approach to spirituality and cultural eclecticism.

Musafar’s reactionary aesthetic rested upon the inextricable link between Western identity and the “savage other” and “civilised self”. What is defined as the attributes of a subordinated other inevitably become a problematic property of one’s own behaviour; the ‘other’ (savage), although peripherally positioned ‘out there’, has become a repressed and denied feature within the controlled, regulated, medicalised, religious body. Apropos a crisis of meaning, Musafar used his imagined primitive to reconstitute the body as he perceived it before Christian and scientific interference—a vessel for spiritual exploration.

Such narratives have historically been complicit in the oppression of Indigenous spiritual systems and communities. Romanticising practices and exaggerating otherness only serve to obfuscate oppression and indigenous efforts to reclaim tradition. Consequently, the representation of who speaks and who is heard about spirituality and the sacred is political. The recent revival of traditional tattoo and modification practices among indigenous communities across the globe is a response to the knowledge that the culture they practice is not their own but one that was forced upon them. The phenomenon has presented both challenges and opportunities to renegotiate cultural agency and empowerment where ultimately progress is now led by the cultural group themselves.

Although Musafar’s primary aim was to highlight the power of body modification ritual, his analysis failed to consider that, even as an individualised practice without “primitive” ritual or codified meanings, body modification and tattoo requires undergoing painful procedures and internalising a new, visually different sense of self—the phenomenological effects of which can indeed facilitate a profoundly transformative and sacred experience.

Footnotes:

[1] This book was not, as many incorrectly claim, the first book to bring full-body tattoo or body modification practices to a Western audience. Arnold Rubin’s Marks of Civilization (1988) was among the first systematic and cross-cultural attempts to present a diverse range of indigenous bodies engaged with varied forms of body modification in one book. Much of the research presented was based upon academic ethnography. In 1983 Ed Hardy and Leo Zulueta published the now infamous first issue of Tattootime, entitled New Tribalism. The book featured full-body tattoos, many of which were predicated upon Polynesian motifs. It was said to have inspired the tribal tattoo style movement in the West. Before that, in 1979, Spider Webb had published Pushing Ink: the fine art of tattooing.

[2] His rendition of a Native American Sundance ritual is a particularly cringeworthy example.

[3] Despite being heavily Christianised, Samoans managed to retain much of their customary tatau practices, social organisation, and political structures, a true testament considering the missionaries’ pervasiveness.